|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

This site is supported by

Friends of IAGenWeb |

|

| site search by freefind | advanced |

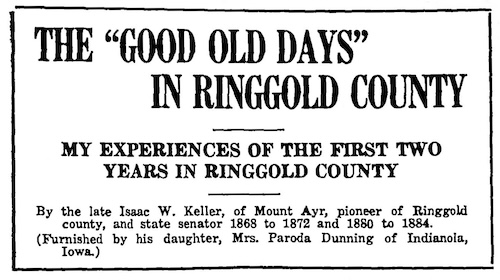

The "Good Old Days"

In Ringgold County

My Experiences of the First Two Years In Ringgold County

By the late Isaac W. KELLER, of Mount Ayr, pioneer of

Ringgold county, and state senator 1868 to 1872 and 1880 to 1884.

(Furnished by his daughter, Mrs. Paroda DUNNING of Indianola, Iowa.)From the Mount Ayr Record News, March 18, 1925

I came to Ringgold county, June 5, 1855, and selected land in what is now Jefferson township. Immediately after selecting my land I went to Chariton to purchase it. Chariton was then a village of 300 to 400 inhabitants. The buildings were mostly log houses. After entering my land, I returned to Clarke county, where my family was, and then moved to this county, arriving June 10, 1855. There were a few settlers that vicinity, among whom were Michael BEVER, Mrs. BEVER, James FRAIZER, Luke SHAY, Asa AMES and Joseph QUINN. My family at that time consisted of my wife, my daughter Paroda, now Mrs. Day DUNNING, and myself. We drove to the timber on West Grand river, set a pole against two trees and drew the wagon sheet across it which served as small tent in which we lived for three weeks, until I could erect a log cabin on my embryo farm.

Our first meal eaten in the county was composed of corn bread, bacon and coffee and was spread on a table composed of the tail gate of our wagon box placed across a log. As soon as our tent was comfortably fixed for habitation, I commenced to cut logs for a cabin, with a roof of split boards. We moved into it and lived a little more aristocratically. There was an opening for a door but no shutter, a window without sash or glass, a good solid floor composed of the ground, and a chimney built of blocks of prairie god. We had no furniture of any kind. We cooked our meals over a wood fire. For chairs we used small boxes and benches. For bedsteads we used a pole reaching from one side of the cabin to the opposite side, and on this pole and a log in the side of the cabin we placed split boards upon which we placed our beds, on which we slept soundly and rested very well, having plenty of fresh sir, and plenty of water when it rained. Our table was made of the lid of a large box in which we had shipped our goods. In this way we lived during the summer on the best the country afforded, such as corn bread, bacon, coffee, slough water and such wild fruit as we could find.

During July I succeeded in getting about 30, acres of ground broken, but could grow no vegetation that year. We lived contented and happy that summer and fall dreaming what the future would bring forth, and occupied our time in preparing for the approaching winter and raising a crop the next summer. Indians and wild beasts were plentiful, such as deer, wolves, turkeys, prairie chickens, and squirrels. Elk had been numerous and large, perfect, elk horn were scattered over the prairies. Wild fruits, such as plums, grapes, crab apples, cherries and choke cherries were plentiful. Of these we manufactured our delicacies, although sugar and syrup were difficult to get for the want of money to purchase them. We therefore had to resort to sorghum, pumpkin or watermelon molasses, which answered as a very good substitute.

There was an abundance of grass all around us; in fact, the prairies were an unbroken plain or sea growing grass and many of us lost thousands of dollars by not having cattle to eat the grass. The Indians were peaceably inclined so far as I could observe. They lived in a town about four miles southwest of my place, and could be seen any day on the prairie or in the timber hunting. They frequently called at our house for such things as we felt disposed to give them. During the summer a man was killed on Sand Creek, of which the Indians were accused, and which created quite an excitement. For two weeks we were organized in a small army to protect our homes and families. At the time this man was killed I was away from home. The report having gone to other counties east of us that we were being murdered by the Indians, companies of men came to assist us. The Indians were corralled and forced to go to Kansas. Thus ended the Indian war. There were many ludicrous and funny incidents occurred during this trouble which I might mention if they were not so absurd.

After the Indian war and peace and quiet had been restored, we again set about to prepare to meet the rigors of the approaching winter, which proved to be a very cold one. During the first summer and fall we went to Eddyville and Oskaloosa to get meal, flour, meat coffee and such articles as we had to have. We would take one or two yoke of oxen and be gone on one of these trips from six to eight days, letting our oxen graze mornings and evenings and we would eat corn bread and meat and drink slough water.

We lived contended and happy during that summer and fall. When the winter of 1855 set in about September 15, it snowed and blew almost continually until the last of February. Our cabin was plastered with mortar made of black soil, and when it dried was full of small cracks, through which the wind and snow would drift. The roof of the cabin was made of split boards and the strong wind would drive the snow under these boards so that everything in the cabin would be covered with snow. I remember one night it snowed very hard and in the morning there was about four inches of snow on the floor and beds. I had to get out of bed into this snow in my bare feet, dress and build a fire and clean up the snow. But I think I dressed about as quickly as I ever did. By this time I had made a floor in our cabin and made a set of chairs, two rocking chairs, a table and two bedsteads, using the cabin for a work shop. After this snow storm we used some rag carpet we had brought with us, stretching it across the joists over head to protect us and our new furniture from future storms. But notwithstanding all our efforts, we suffered severely from the cold. From the middle of December till the last of February there was no day that the snow melted on the south side of our cabin. There was a continuous stream of northwest wind, the snow was 12 to 16 inches deep and was continuously changing its location. I hauled a load of wood every second day. Notwithstanding the amount of wood we burned, in order to keep warm we had to put quilts on the backs of our chairs so that our backs would not freeze while our faces were almost burning. It was so intensely cold that we could not work in the timber to prepare material for fencing our land. Notwithstanding these hardships, we were contented, and looked forward to better times and milder winters.

When spring came we commenced work in earnest, chopping timber, making rails, and getting ready for a crop. I planted 25 acres of sod corn with plenty of watermelon and pumpkin seeds mixed in. But the summer being very dry, I did not raise much corn. But we had an abundance of delicious watermelons and some pumpkins. We manufactured the melons into syrup with which we made plum and grape butters and preserves. I had succeeded in growing some potatoes and other vegetables and we then lived very sumptuously.

In those days we had very good society. All were on an equality, neighbors very kind and sociable, all lived and dressed alike. We cared nothing for ornamentation. The men went to church in the summer without coats, some without boots or shoes. We had no buggies or carriages in those days. When it was too far to walk to church we put a yoke of oxen to a wagon and rode. If any one had no wagon box, he would put a board on the wagon and ride the on board. When church closed all were invited to stay for dinner which most of us did. The first two years meetings or this character were held in private houses, first in one and then in another. When there was no church on Sunday we would all visit someone of the neighbors and have a good social time. We thought nothing of the hardships and privations we endured, but had faith to believe that a better time was coming.

Mail facilities were not good. My first post office was at Hopeville. When an office was established at Afton I changed to that place. Afton was then a very small place with a few log houses. Mount Ayr had been surveyed into lots about four or five weeks before I came to the county, and had but one log cabin. I did not go to Mount Ayr until the spring of 1856. There were a few log cabins then. I purchased such things as we were compelled to have first at Hopeville, then at Afton, frequently walking there and back.

After the second year I did my trading at Mount Ayr, often walking from my place and back, a distance of 24 miles, in a half day.

I sowed some spring wheat in 1856 but on account of dry weather and the sod not being properly rotted, it did no good. Therefore we were compelled to purchase meat and flour for another year. But having raised many kinds of vegetables, we got along nicely and put aside supplies for the winter 1856. By this time we had gotten some cattle, hogs and chickens and began to have the appearance of a thrifty farmer. A goodly number had settled around us and neighbors were more convenient. We got pretty well prepared to go into the winter of 1856 and 57. It was a cold winter with heavy snow, but not so cold as the former one, and being better fixed and knowing what an Iowa winter was like, we had fortified ourselves to endure it with less suffering.

Doctors were scarce in those days and traveled a long distance to see their patients. In the spring of 1857 my wife was taken sick and continued to get worse until she was unable to get around. I sent to Hopeville and other points for a doctor, but could get none to see her. Grain was not to be had and the doctors could not use their horses. I did not know what to do. My wife was getting worse and I expected she would not live long. I was in the field plowing when thought of a medical work called Howard's Domestic Medicine that I had traded for the year preceding and had never examined it. I immediately tied up my team, went to the house, got my book, and commenced to peruse it. Finally I came to where it treated on scurvy and after reading the description of scurvy I went to the bed where she was lying and said, "I believe I know what is the matter with you." I then read to her the description of scurvy and she said it was a correct description of her disease. The

book prescribed a vegetable diet, acid drink, such as lemonade, etc. I immediately applied the remedies and in a few days she was much better, and in a short time able to be up and around. A few days thereafter, while in the field plowing, a man came to me and said, “I want you to come and see my sick wife.” I told him I was not a doctor. He said he had heard that my wife had been sick and that I had treated her and that he had a doctor to see his wife who did her no good. I asked him some questions in reference to his wife and then told him that she had scurry and told him what to give her. He then insisted that I go and see her and treat the case. I told him I was not a doctor and he could treat the case as well as I could. A few days later another man came to me and wanted me to go and see his sick wife. I told him I was not a doctor, and he replied that I had treated my wife successfully. I made some inquiry of the nature of the disease and then informed him that she had scurvy and told him what to do for it. Both of my patients got well. Had I embraced the opportunity then offered and gone and treated these cases and used some terms people did not understand and continued to answer calls, I might have been an eminent physician in those days.

In the summer of 1857 we had good crops. I raised four acres of wheat and threshed 101 1⁄2 bushels. After that time we had plenty of good wheat bread and all the vegetables we could use, and had no more scurvy.

I have lived to see Ringgold county settled, a happy, contented and industrious people, intelligent and enterprising, whom I greatly admire. In conclusion I will say that I know of no other place that would rather live than in Ringgold county.

Transcription by Tony Mercer, February 7, 2025

The "Good Old Days" is a series of articles that appeared in the

Mount Ayr Record News in the 1920s about the early history of Ringgold County

Articles in this series:

Five Negroes and A Dog Funeral

Indian War of 1855

When Mount Ayr Was Wet

My Experiences of the First Two Years in Ringgold County

When Saloons Cursed Mount Ayr

How Pioneer Mount Ayr Met the Rebel Guerrillas

The Modest Styles of Long Ago

A Kidnapping Incident in Early History of Ringgold County

Early History of Ringgold County Settlers, Part 1

Early History of Ringgold County Settlers, Part 2

Thank You for stopping by!

© Copyright 1996- Ringgold Co. IAGenWeb Project All rights Reserved. |