THEY DEFY ENTIRE JAP NAVY

Jack Stoos Mans One of Heavy Machine Guns

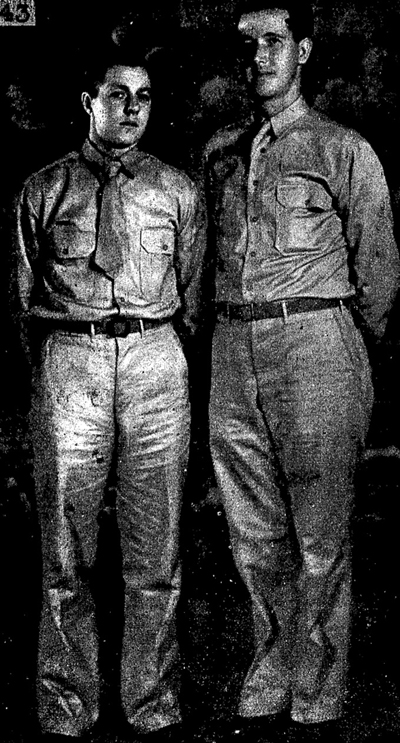

Matt Ruba on the left & Jack Stoos on right

Among the sagas of heroism that adorn the pages of American military history, co-equal with the siege of the Alamo, are Wake Island, Guam, and Corregidor, and when the final story is written, history will probably say that Corregidor was the most crucial.

Today, at least two Plymouth County men are doing the job at Corregidor. They are Mathias Ruba, son of Mr. and Mrs. Matt Ruba, of Marion township, and Jack Stoos, son of John Stoos, of Remsen.

Both enlisted in the United States army in December, 1940, and until the war broke out, the copy of The Globe-Post for which young Ruba had subscribed was being sent to Fort Mills. It’s a safe bet that he hasn’t been getting his paper regularly lately, and also that he would be too busy to read it anyway, what with having to dodge Japanese bombs, and sending back to the Japs large and noisy shells loaded with unpleasantly acting T. N. T.

Corregidor is the key to Manila Bay. Unless the Japs can capture it, their costly conquest of the large Philippine islands of Luzon, and even the capture of the city of Manila, will be of little military benefit to them. Every since Dewey sailed into Manila Bay to destroy the Spanish Navy, Corregidor has been recognized as the key to all the Philippines. In a way, it is the key to all of Australasia—though not the only key.

Matt Ruba is now a sergeant in charge of the feeding of the men who serve the guns at Corregidor. After his enlistment, he was offered an opportunity to attend an army cook’s and baker’s school. He made good there, received his sergeant’s warrant, and in subsequent inspections his kitchen received the highest rating for efficiency and cleanliness on the island. If any Jap bombs dropped on it, it may be not quite so neat now, but at any rate, Sergeant Ruba hasn’t been seriously wounded or killed up to now.

Mrs. Elmer Nitschke of Remsen, sister of Jack Stoos, told The Globe-Post Tuesday that Jack had written little except personal news since he was sent to the Philippines; except that he had been assigned to a machine gun company on the island. From this it can be deduced that he is today living in a red rock cave, fairly well protected by sandbags and solid concrete breastworks, the muzzle of his heavy, 50-calibre machine gun, forever scanning the waters of Manila Bay for possible sneak attacks by Jap suicide squads in small boats, trying to get to the island under cover of darkness.

Little information of actual conditions in Manila Bay has been published, due to military secrecy. However, stories of some war correspondents indicate that Corregidor has not been attacked from the Batan peninsula, where a heavily outnumbered American-Fillipino army is still holding out. Neither is it likely that any Jap submarines have tired to land storm detachments, because the navigable water is heavily mined and also closed by submarine nets.

Except for some long distance artillery dueling, and one or two attempts by Japanese warships to force the passage—attempts that cost the Japs heavy losses from the booming big coast defense guns on the island, all of the attacks on Corregidor island have come from planes, by air.

Corregidor originally was not designed to resist heavy aerial attack. Its high, steep-sided red rock walls were honeycombed, however, with tunnels and underground rooms to give its gun crews protection against heavy bombardment from the sea, and this protection is just as good against bombs. The Japs can bomb until they’re black in the face—instead of yellow—and the men resting underground will hardly hear them.

On top it’s different, of course. It’s a safe guess that anti-aircraft guns were taken off some of the ships evacuated from Cavite, and set up on Corregidor, and these are certainly in heavy action. Young Stoos, as machine gunner, is probably firing at the Jap planes every chance he gets.

The real show-down on Corregidor is not likely to come unless the Japs can force General MacArthur to evacuate the peninsula of Batan and cross the shallow waters of the bay for a last stand on Corregidor.

Whether this will come before several months seems doubtful. The cost to the Japanese of a final assault would be extremely bloody losses, and they may decide on a long siege in the hope of starving the Americans out. In the latter event, there is good chance that President Roosevelt may decide to launch a counter-offensive, and the tough garrison of Corregidor, like that of Tobruk, may be able eventually to leave its stronghold and return home, where the members including the Plymouth Countyans, will receive the honors due to heroes.

~Source: LeMars Globe-Post, Thursday, January 15, 1942 (photograph included)

![]()

PLYMOUTH COUNTY MEN WAR PRISONERS

Reports of war causalities are becoming more frequent and several Plymouth County service men have been reported killed. The last few days reports from both Africa and the Southwest Pacific areas have added information as to men first reported missing who are now definitely known to be prisoners.

Willard Stearns, who had several years service with the Marines and was at Shanghai a few days before war started, was first reported missing but is now definitely known to be a prisoner of the Japs at Taiwan. His parents, Mr. and Mrs. Frank Stearns, moved from LeMars to Des Moines after he entered the service.

Joseph L. Wetrosky, living west of Kingsley, received a telegram Monday from the War Department in Washington, D.C., that his son, Joseph L. Wetrosky, was missing in Africa in the period of February 17. He went into the army two years ago, and was among one of the first groups overseas.

First Class Private Mathias M. Ruba, son of Mrs. Lena Ruba, of LeMars, was announced by the war department Thursday as being a prisoner in the Philippines.

William Bastian Westerberg, 22, boilermaker, second class, is a prisoner of the Japanese, the navy department has notified his parents, Mr. and Mrs. John Axel Westerberg, of Hinton. Young Westerberg was born and raised in Sioux City. He attended school here and was graduated from Hinton high school. He is a grandson of the late W. H. Bastian.

Source: LeMars Sentinel, March 16, 1943

![]()

Mrs. Lena Ruba Learns Son At Another Jap Prison Camp

He’s On Island of Kyushu Off the Coast of Korea.

Mrs. Lena Ruba has received word from the U.S. War Department informing her that her son, Pfc. Mathias M. Ruba, who was captured by the Japanese after the battle of Corregidor, has been transferred from a prison camp in the Philippine Islands to a camp called Fukuoka, on the southern Jap island of Honshu, which lies across a narrow strait from the mainland peninsula of Chosen (Korea.)

The southern most large island of the Jap archipelago is Taiwan (Formosa) which really belongs to the Philippines group, and is mostly wilderness. Honshu, however, is well populated.

Mrs. Ruba was somewhat concerned by the news of the transfer because Math has been getting along fairly well in the Philippine camp, and was resigned to staying there until the war is over, and it was feared here that the transfer might be for the worse.

According to an article in the current American Legion, however, it would appear that the change should be for the better. In an article, “Johnny, Doughboy, Prisoner,” this magazine, after describing satisfactory prison camp conditions in Germany, says:

“It must be borne in mind, however, that all that has been said herein applies only to the German and Italian camps housing United Nations prisoners of war. The best that can be said for the Far East is that the prisoners in the camp near Shanghai, China, and those in camps near Tokyo are faring not too badly. What the conditions are in the Philippines is not known, for the Japs have refused representatives of the I.R.C.C. permission to visit them on the grounds of Japanese nation security.”

The camp from which Pfc. Ruba was moved was one of the uninspected Philippine island camps. The camp to which he has been removed is just about half-way between Shanghai and Tokyo.

Source: LeMars Globe-Post, October 14, 1943

![]()

Mrs. Matt Ruba has received word from her son, Norbert, informing her that he is already at the fighting front, in Belgium. He has been assigned to the infantry. No word has been received for some time from her other son, Matt, a prisoner of war of the Japanese since Corregidor fell. He is on the main Japanese island of Honshu.

Source: LeMars Globe-Post, February 22, 1945

***Further Research:

Mathias Michael “Matt” Ruba was born Jan. 2, 1918 to Matt and Magdalene “Lena” Kramer Ruba. He died Nov. 9, 2012 in CA. He was a Japanese POW for 3-1/2 years and in the Bataan March.

Source: ancestry.com

![]()