Army Buddies "Light Up Like Christmas Trees" When Reunited After Nearly 42 Years

After not knowing what had happened to each other for nearly 42 years, Ludvik Mayer, 70 ,Chelsea and Norman Meyer, 68, Paullina (in Northwest Iowa) had a fun weekend June 28 to 30 rehashing old times at Mayer's Chelsea home.

The two army buddies were separated in February of 1944 in Hawaii and neither knew the whereabouts of the other until this May although they lived in Iowa since they returned home from the service in 1945.

They discovered each other was alive when there was an article in the Disabled American Veterans Magazine about their old company planning a reunion. Mayer contacted the organizer in Tennessee and got Meyer's address and phone number. He called Meyer about six weeks ago and immediately set up a reunion of their own. "I wanted to see him immediately," Meyer commented.

Christmas Trees

What was the reunion like?

Mayer's wife said Ludvik was pacing the floor anxiously awaiting the arrival of his old army buddy Friday afternoon. Finally the Meyer's arrived.

"The looked like two Christmas trees that just had been plugged in," commented Meyer's wife, Nell, Saturday morning. "They shed a few tears and have been smiling ever since."

"Too bad I had to give up drinking," commented Meyer, noting that they had enjoyed a few drinks together in the Army.

"They are so tickled to see other," added Mayer's wife, Evelyn, "That makes us happy. We are learning a lot of interesting things that we did not know before."

"I've just met these people (the Meyer's)," Evelyn added, " and I feel like I've known them all my life."

Mayer and Meyer are a couple of the fortunate soldiers who survived the Pacific Theatre battles. their old army unit, Company K of the 27the Infantry Division, had 75% casualty.

Mayer and Meyer both were inducted into the Army at Camp Dodge in Des Moines in October of 1941 and became best of friends during boot camp at Camp Walters, TX. Norman entered the service on Oct 6 while Ludvik entered Oct 20.

They had not yet finished training when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. They were almost immediately transferred to Fort Ord, CA for further training for about two weeks and then on to San Francisco where they boarded the USS Lurine, a passenger ship converted into a troop ship, to begin the 5-day trip to Hawaii.

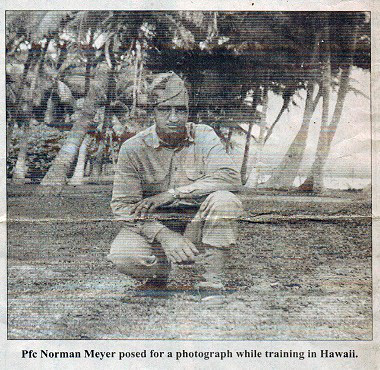

They spent seven months on the big island, Hawaii, in additional training and then another seven months on Oahu where Honolulu is.

"We were among the fist troops to go overseas after the war broke out," Mayer commented. He noted that when they arrived at San Francisco they joined Company K of the 27th Infantry Division which was originally the New York National Guard.

Both men carried the Browning Automatic rifles (BAR's) which was a small machine gun. "Our gun and field packs weighed 78 lbs," Mayer recalled.

As they were loading up to attack the Japanese on the Marshall Islands, Meyer cracked an ankle, loading artillery shells onto the ship. That day, in mid-February of 1944, was the last he saw of Mayer who departed while Meyer had to stay behind to recover.

Mayer was injured during the battle of Emiwetok Atoll Island between Feb. 18 and 24, 1944. He was on the hospital ship when Company K returned to Hawaii and then left again this time with Meyer leaving to join the battle while Mayer recovered.

Mayer was in the Army hospital at Hawaii for three months as gangrene had set in. That infection left his trigger finger stiff and he was never again in battle.

"I really wanted to join the rest of my company on the front lines, but with a stiff trigger finger, they would not let me go," Mayer stated. For the rest of his Army career, Mayer was in the detached service working in the Army PX in Hawaii.

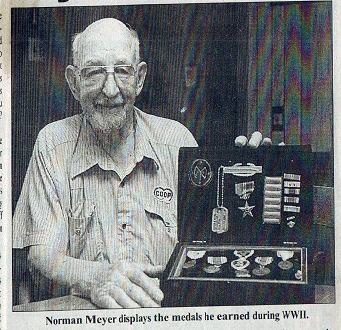

He was awarded his purple Heart on Jan. 5, 1950, but didn't receive his Bronze Star until April 19, 1984, after writing for it.

Meyer injured twice:

Meyer, a life long resident of Germantown, 7 miles southwest of Paullina was wounded twice. He was fist hit in the Western Pacific Theatre on Aug. 23, 1944, on Saipan Island. One week later he was back on the front line. He earned the second purple Heart when he received a concussion on Okinawa on April 19, 1945. After 10 days in the hospital he was back on the front line again until the war ended.

Both men were processed at Jefferson Barracks, MO, when they were discharged in October, 1945, but their paths didn't cross again last Friday. Meyer was discharged Oct. 2, while Meyer was discharged Oct 6, just 2 days short of 4 years. He noted he never had a furlough during the entire time in the Army.

What are some of the memories that they hashed over last week end?

Both vividly recall seeing the disabled U.S.ships in Pearl Harbor in 1945.

Other than their injuries, they also recounted some good times while in training and their first arrival in Hawaii.

"It was like paradise," Mayer commented. Meyer has since returned to Hawaii and finds it still very beautiful but far too commercialized. Both would like to return to the Islands where they were wounded.

Meyer recalls 19 straight days of rain without shelter other than his foxhole while on the front line. After many days of wet socks and shoes, he finally got a dry pair of shoes. When he took off his wet socks, his skin on the bottom of his feet came right off with them, due to being wet so long. As he was walking to the canteen a short time later, they were nearly hit by enemy fire so he had to jump into a ditch filled with water up to his chest. That was the end of his dry shoes.

"What I hated most was the nights," Meyer recalled. "I just dreaded it and hated going back on the front line after being wounded. I just wanted to get out of there."

Mayer said one of his most vivid memories was when he jumped into a former foxhole and landed on something soft. Thinking it was a Japanese soldier, Mayer said he got out of the foxhle just as fast, only to find it was only a field pack left behind by the enemy.

After leaving the service, Mayer returned to his hometown on Chelsea to resume farming. He and Evelyn married in March of 1951 and lived in their Chelsea home ever since. "I was a town farmer," Mayer noted.

They have two daughters They have four grandchildren.

Oddly both men had heart problems the same year.

Mayer had heart surgery in 1976 and Meyer had a heart attack in 1976.

Meyer returned to his hometown of Germantown where he operated a truck business for 27 years before retiring in 1971. He met his wife, Nell, a Calumet telephone operator, shortly after returning home and they were married in 1946. They have five children and 10 grandchildren.

Looking back to when he first came home, Meyer said he was at first glad to be home but then was very homesick for his Army buddies.

"I wanted to get back with the boys," he commented. "on my first day home I could have gone back with the boys if we could have all been together again."

Mayer said he felt the same way and his wife notes that since they were married he has commented often that he wished he could get together with his Army buddies.

Meyer is planning to attend Company K's reunion in Tiptonville, TN Aug. 16, 17, and 18. Mayer would like to go but notes his wife is saving vacation time for when their daughter gets married in September.

The Meyer's were treated to great hospitality by the Mayer's.

Source: Paullina Times-Sutherland Courier, Thurs. July 18, 1985

Reprinted from The Tama News-Herald

[Contributed & transcribed by Kris Meyer]

![]()

Norman F. Meyer (1916-1996)

war is hell-no matter what side you are on....

"War is hell," reflected 78-year old Norman Meyer of Germantown.

He skirted death on several occasions while fighting for his life and the future of his country during WW II. He devoted nearly four years to the United States Army. Of those four year, three and one-half were spent battling the fierce Japanese in the South Pacific.

Meyer's Army Unit-Company K of the 27th Infantry Division- fought major battles on Saipan Island and Okinawa. He was injured twice and was awarded the Purple Heart with oak leaf clusters, the Bronze Star, and other medals and awards.

The efforts of those who served were not without sacrifice, however. Tears filled Meyer's eyes ad his voice wavered as spoke of his buddies lost in action. Company K suffered a casualty rate of 75 percent.

Meyer knows he's fortunate to have lived to tell about it.

He grew up in the Germantown area and graduated from the seventh grade at St. John School. Meyer worked on area farms until he was drafted in October 1941.

He was inducted into the Army at Camp Dodge in Des Moines and spent 16 weeks in boot camp at Camp Walters, Texas. "We were just about done with basic training when the Japs hit Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941," recalled Meyer.

He and his fellow soldiers were transferred to Fort Ord, California for two more weeks of training and then sent to San Francisco where they boarded the USS Lurine to begin a five day trip to Hawaii.

"It was a passenger ship that had been converted to a troop transport," said Meyer. "It had a swimming pool but it was all full of bunks so they could haul more troops."

Company K spent seven months training on the "Big Island," and then another seven months in Honolulu on the island of Oahu.

As the troops were preparing to attack the Japanese on the Marshall Islands, Meyer cracked an ankle loading artillery shells onto the ship. He was forced to stay behind to recover.

After Company K returned to Hawaii from the Marshall Islands, the troops were sent to Saipan Island. "When we landed, we had to walk a quarter mile through the water to reach the beach," said Meyer. "the closer we got, the worse the smell was. The smell was unbelievable. There were dead Japs and Americans lying on the beach in the hot sun. Human being is the worse stink there is."

It was August 29, 1944, when Meyer was injured. He and the rest of Company K had moved up to the front lines on Saipan. Meyer carried a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR), which was a small machine gun. His gun and field pack weighed nearly 80 pounds.

He spend a few days in the hospital and wrote home about his experiences: "I was in the battle of Saipan and I hope things never get that hot again. I don't know if you heard that I got hit. I didn't' get hit too bad. I was digging in close to a Jap munitions dump when they threw everything they had to blow her up, and they did. That's the time I thought all hell broke loose. That's when I got a concussion and small pieces of shrapnel in my face. I couldn't see or hear very good for a couple days. My right ear was badly pierced.

"Boy, were the Japs ever dug in the caves, the only way to get them out was to go in after them. The snipers were the worst thing, and they are all over and you can't see them. One day a sniper put two holes in a tree just above my head. Boy, it was time to move and I don't mean maybe.

"I thought of times when I was home and things were tough, but I was lucky and didn't know it.

"When you lay in a fox hole at night with a knife in one hand and a rifle in the other, you age one year every hour, and you pray like you have never prayed before. I could sit and write all day, but if you think you got it tough at times, think of a person in a fox hole on the front lines. Brother, he's got it tough...."

Meyer, in a sense, respected the Japanese soldiers. "They were smooth fighters- actually they were better fighters than we were," he admitted. "They wore thongs and were real good sneakers- real quiet.

"A good friend got a direct artillery hit one night," added Meyer. "His flesh flew all over us. You get tears in your eyes and you wipe them off and keep right on going.

"There was fear all the time - constant fear all the time. You never knew when......" His voice trailed off and he quickly changed the subject.

"The first night we were on the island, a Jap bomber- 'Washer Machine Charlie' - came over," reflected Meyer. "he was dive bombing us and hit an artillery piece on shore- killed eight men." The Japanese bomber flew over Saipan every night and always managed to avoid being shot down.

"The night before the fighting ended on Saipan, the Japs pulled a banzai attack and broke through some of our lines," noted Meyer. "The next morning we had them down in a valley. They were surrounded and killed. They were out of ammunition, but wouldn't surrender."

Eventually the soldiers were sent to the New Hebride Islands, west of the Fiji Islands. Rations on the ship during the trip were scarce- every morning the troops were given rice for breakfast. "The first morning there were white worms in it," reflected Meyer with a grin. "I picked out all the worms. The next day I was standing there picking out the worms, and I said to the guy next to me, "Isn't this terrible- these worms?"

"'Gosh,' he said. 'It's good fresh meat.' He ate them and so did I. I always ate them every morning from then on."

Company K was among the troops who spent seven months on the New Hebrides Islands in training. They learned later that it was in preparation for Okinawa.

"I never saw a town on New Hebrides," said Meyer. "All I saw were head hunters with rings and bones in their noses and ears. At night, if it was real quiet, you could hear them beating on their drums up in the mountains.

"A guy from another company always wanted someone to go with him up in the mountains to see what the head hunters were doing," observed Meyer. "One night he went alone and never came back."

Meyer and his fellow soldiers arrived on the Island of Okinawa on the second or third day of combat. They moved up to the front lines.

"One day we were on top of one hill and they were on top of another hill," noted Meyer. "We were under some trees and their artillery would land behind us. That night they moved their artillery and the next morning the shells landed in our trees. It was April 19, 1945 and Meyer was injured for the second time.

"One of them (artillery shells) landed close to me and tore all my clothes off. I woke up in a cave that night."

As Meyer was being carried from the cave and across a creek, a Japanese soldier opened fire with a machine gun. "They dropped me, just about in the water and ran," said Meyer. Miraculously, he didn't get hit.

After recovering from a serious concussion, Meyer was sent back to his company. "We just kept on fighting," he said. "We started mopping up- there were a lot of Japs in the hills and mountains."

Rations and drinking water were in short supply in the island mountains, Meyer said the soldiers would hang helmets in the trees at night to catch rain water. "One time they got water up to us in five gallon gas cans," Meyer reflected. "Gas was floating on top of the water. Do you know what kind of diarrhea you get? Terrible."

Then there were times when there was literally too much water. Meyer recalled 19 straight days of rain without shelter other than his foxhole on the front lines. After many days of wet feet, he was finally issued dry socks and shoes. When he pulled off his wet socks, the skin on the bottom of his feet came off with them.

A short time later, Meyer was sent to a rations truck down in a valley to help carry supplies. As he was making his way down the mountain he was nearly hit by enemy fire. To avoid flying bullets, he jumped into a ditch filled with water up to his chest. That was the end of his dry socks and shoes.

Meyer said he hated the nights. The Japanese troops would carry knives in their teeth and crawl up to the American fox holes. "If we didn't catch them, they would stab the guys in the holes," he reflected. Have you ever heard a death scream at night? When its quiet?"

But then somebody would shoot them...it was an honor for the Japs to die for their country.

"When I laid down at night, I had my bayonet in one hand and my trench knife in my other hand," Meyer added. "I don't know how I ever went through something like that."

What kept Meyer and his buddies going?

"I don't know- the good Lord I guess-done a lot of praying," he reflected. "You always had friends right next to you, that were in the same boat you were."

Frequently the U.S. troops measured their progress in Okinawa in hills. Meyer vividly remembers one particular battle over a hill.

"The Japs were in caves with steel doors. They would open the doors and shoot hell out of us and then close the doors and our artillery couldn't hurt them," he observed. "One day the weather cleared enough for the fighter planes to come in."

The planes dropped napalm "jelly bombs" on the Japanese. "Jelly bombs were hotter than a sheriff's pistol. Oh they were hot. When they hit the trees, fire flew all over the place," Meyer observed. "Later, we found dead Japs in the caves- they were fried."

Meyer chuckled as he remembered a new replacement that joined Company K in Okinawa. He was 19 years old. In broad daylight, he would run out and make a circle to see if he could draw machine gun fire.

"He'd go to beat hell," laughed Meyer. "And every dead Jap he found, he'd knock the guy's gold teeth out and put them in his pocket. One day, he rolled a dead Jap over and it had a booby trap underneath. It blew the kid's leg off. I never saw him again. but that kid had guts. Oh, he was a fighter. He had guts."

"Sounds like he was a little loose somewhere," noted Meyer's wife, Nellie.

"But he kept our morale up though- a guy like him," said Meyer.

Inevitably, there are innocent victims of war.

Meyer still cries when he talks about an Okinawa native mother and her child who happened to pass by the wrong place at the wrong time.

Company K had been held up in the mountains for a few days. Meyer and two other soldiers were put on a trail that led to a stream and then up one side of the mountain. Every night, Meyer ran down the hillside and jumped across the stream and tied a hand grenade to one of the trees. He then tied a string to the pin of the hand grenade and stretched it across the trail to serve as a booby trap for Japanese troops.

One morning, Meyer heard the pin fly off the grenade and explode. He jumped up and grabbed his gun and was going to start firing. Then they heard a child crying.

Meyer's buddies covered him while he went to investigate. He found an injured woman and child.

"That woman had a great big hole in her back- you could see ribs," explained Meyer, his voice trembling. "The kid was tied to his mother's back and had holes in his legs and feet and cuts on his face."

"I went down the hill to pull the child from his mother and the mother turned her head and said something to the child. And the kid started bawling and the mother's head dropped away- she was dead," he continued as he wiped the tears from his eyes.

Meyer couldn't bring himself to tear the child away from his mother, so he went for help.

"The captain came and he called an ambulance. They got the baby away from the mother- the kid was screaming and crying. The captain looked at us and said, "Well boys, you've got work to do."

Meyer and his buddies buried the mother and made a wooden cross out of sticks. "We killed her," said Meyer softly, looking down at his hands. "My hand grenade got her."

He never learned what happened to the child.

When Okinawa was called secure, Meyer and the rest of Company K picked up and prepared to invade Japan.

"None of us wanted to invade Japan." He paused and once again, tears filled his eyes.

"There wasn't one of us that wanted to go, because we knew we had to fight women and children. Anyone would defend their own country, wouldn't they?" noted Meyer.

"But then they dropped the atomic bomb and it was all over."

Meyer was discharged from the Army on October 6, 1945- just two days short of four years of service.

He returned to his hometown of Germantown where he operated a corn shelling and truck business for 27 years. He retired in 1971 and has been working part time for Bunkers Feed and Supply in Granville.

He met his wife, Nellie, a Calumet telephone operator, shortly after returning home and they were married in February of 1946.

"She was hard to date," laughed Meyer. "Oh she was hard to date."

"Well, with millions of servicemen home from overseas, you had to be a little careful," Nellie retorted with a smile.

The couple has one son and four daughters, 13 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

Meyer fought for the future of the country- his children and their children. It was not without sacrifice, yet he would do it again.

"All of us guys, we just hung in there," he reflected. "There were times you would have liked to shoot yourself to get out of there."

Although he hated what they did to Pearl Harbor, Meyer has no grudges against the Japanese. "After all these years, you realize they are people too- they are people just like us," he noted.

War is hell-no matter what side you are on.

Source: News from South O'Brien County

A section of Paullina Times and Sutherland Courier

Thursday, August 3, 1995

![]()

Norman Frederick Meyer was born Sept. 19, 1916 to Adolph and Ella Schulz Meyer. He died Oct. 20, 1996 and is buried in Saint John Cemetery, Germantown, IA.

Source: ancestry.com

![]()