One of the greatest

engineering feats of modern times was the construction

of a great dam across the Mississippi River at the

foot of the Des Moines Rapids, in front of the City of

Keokuk. Soon after the first white men settled in

Southeastern Iowa, the subject of utilizing the rapids

for the development of water power began to be

discussed. While Lieut. Robert E. Lee was stationed at

old Fort Des Moines he made a report to the war

department, in which he suggested the possibility of

turning the immense energy of the rapids to some

account for the advancement of civilization, and at

the same time improving the navigation of the

Mississippi. No action was taken by the Government at

the time, but in the light of subsequent developments

it reads almost like a prophecy.

People who understood nothing of the practical side of

engineering could not recognize that such a thing was

possible as the harnessing of the rapids and the

development of water power for the use of man. The few

who did understand realized that the undertaking was

hardly practicable then, because the population of the

Mississippi Valley was too sparse to justify the vast

expenditure of labor and capital to carry it out.

Nevertheless, these few were not willing to abandon

the idea altogether and in 1836, while Iowa was still

a part of Wisconsin Territory, a company of local men

and New York financiers was organized to consider the

feasibility of developing a water power from the

rapids.

The first actual effort to utilize the force of the

rapids for industrial purposes was made in 1842, when

a man named Gates constructed a wing dam and erected a

grist mill on Waggoner's Point, on the Illinois side

of the river, a short distance above the eastern

terminus of the present dam. A great ice jam carried

away Mr. Gates' wing dam, but with a persistence

worthy of emulation he constructed another and

continued to operate his mill with power furnished by

the Mississippi. Both his dams were very small and

utilized but a very small portion of the power that

could have been, and has been since generated.

In 1843 Joseph Smith, the Mormon prophet of Nauvoo,

Illinois, had the council of that municipality pass an

ordinance giving him a franchise to build a dam from

the Nauvoo shore to an island in the river to generate

power. But before his project could be carried out

Smith met his death while a prisoner in Carthage jail

and the Mormons left for Utah.

Five years after Smith's franchise was granted the

people of Keokuk became interested in the subject and

some of the leading citizens of that city organized a

company to develop the power. Although the efforts of

that company resulted in nothing toward the actual

building of a dam, the public became inoculated with

the germ and from that time there have always been a

few optimistic individuals ready to predict that some

time, in some way, the power of the rapids would be

brought under control and rendered available for

industrial purposes. Another company was organized in

1865 and kept up the hammering process, trying to

interest capitalists, never for a moment doubting that

some day their dream would become a reality.

In 1868 the United States Government began the

construction of a canal along the Iowa shore through

the rapids, for the purpose of improving the

navigation of the river. It was completed and opened

for boats in 1877. In this canal there were three

locks — the upper one at Galland, the middle lock,

near Sandusky, and the lower lock, at the foot of the

rapids. The cost of the canal was $4,500,000 and about

three millions more were expended on the dry dock and

appurtenances.

Although the Government work was not intended to

develop the water power of the rapids, it served as a

stimulus to interested parties to take some definite

action toward that end. Consequently, in 1871, while

the Government canal was under construction, two

Keokuk men employed an engineer to make a survey for a

dam at their own personal expense. Their idea was to

construct a large wing dam, but the proposition did

not meet with the approval of the engineer, who

advised them that such an undertaking would be likely

to prove unprofitable. The press took up the subject

at that time, however, and awakened general interest

in the subject.

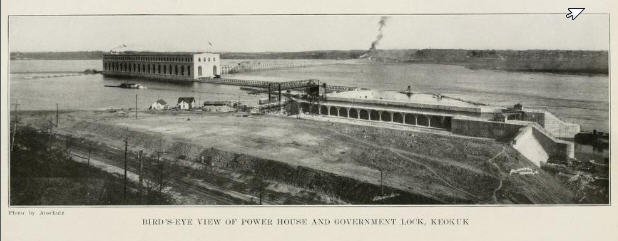

Bird's Eye View of Power House and Government Rock

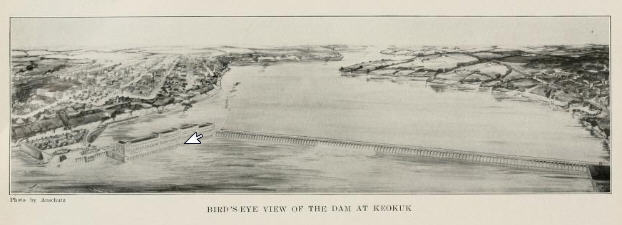

Bird's Eye View of Keokuk Dam

In 1893 came the first suggestion that electricity

might be used to transmit the power generated by water

wheels, but the electric motor was then in an

embryonic state, and until the motor was brought to a

higher state of perfection its use was not to be

considered. Thus matters stood until July, 1899, when

C. P. Birge called a meeting of some twenty-five

citizens of Keokuk and Hamilton, Illinois — just

across the river from Keokuk — to make one more effort

to brins? about the construction of a dam. This

meeting was really the beginning of the Mississippi

River Power Company. In April, 1900, the Keokuk &

Hamilton Power Company was incorporated under the laws

of Illinois with A. E. Johnstone, president; William

Logan and C. P. Dadant, vice president; R. R. Wallace,

secretary and treasurer; Wells M. Irwin and D. J.

Ayers, of Keokuk, and S. R. Parker, of Hamilton,

directors.

This company obtained a charter from the Federal

Government in February, 1901, for the construction of

a wing dam on the Illinois side, and Lyman E. Cooley,

a hydraulic engineer of Chicago, was employed to make

the survey and specifications. Mr. Cooley pronounced a

wing dam impracticable and the company was forced to

abandon its original intention.

In April, 1904, Congressman B. F. Marsh introduced a

bill to grant the Keokuk & Hamilton Water Power

Company the right to build a dam across the

Mississippi River at the foot of the rapids. The bill

passed both houses of Congress at the next session and

was approved by the President on February 9, 1905. In

April, 1905, the stock and franchise of the company

was assigned to and vested in a committee consisting

of John H. Irwin, A. E. Johnstone, William Logan and

C. P. Dadant, with full power to make contracts and

transact all other business pertaining to the dam

project. Concerning this company and its committee,

one of the Keokuk papers said:

"It must not be forgotten for a moment that this

corporation was a quasi-public, quasi-governmental

corporation, outside of, and yet a part of the

political organization of the State of Iowa, as is the

public school system for instance. Its stationery

should have borne the subtitle, 'The Public,

Incorporated.' While it had a trifle of $2,500 of paid

up capital, it handled many times that amount of money

as a public trust, a considerable amount coming to its

treasurer from the municipal treasuries of Keokuk and

Hamilton. There was never in the history of the world

anything like that water power promoting corporation.

It was frankly organized for promotion purposes, as

the representative of the citizenship

hereabouts.

"It operated practically by unanimous consent. Its

officers were men of the two cities possessing the

full confidence of the masses of the people. It did

things to the municipalities that have never been

paralleled and that are among the highest triumphs of

a dominant democracy. It said it needed money at one

time to pay for surveys and other legitimate promotion

work — and the city councils of Keokuk and Hamilton

promptly voted it an appropriation of public money. Of

course this was widely extra-legal ; far from any

concealment, the greatest publicity was given to the

intended action before it was taken; every citizen

suspected of opposition was asked personally, and by

newspaper notice everybody else was practically

invited to stop the action, if they chose, by a very

simple injunctive process. Not a man could be found in

the two towns who had any objection. Every citizen

considered it his own movement, this water power

development movement. It was a movement of the entire

mass acting as a unit."

The Keokuk & Hamilton Water Power Company, through

its committee, prepared a circular pamphlet or

prospectus giving some data concerning the Mississippi

River at the rapids and a statement of their aims and

needs, chief of which was the capital to build a dam

and a competent engineer to take charge of the

undertaking. One of these pamphlets fell into the

hands of Hugh L. Cooper, an engineer who had already

made a world-wide reputation by his achievements in

Jamaica, Brazil, at Niagara Falls and McCall's Ferry,

Pennsylvania. Mr. Cooper came to Keokuk, looked over

the field, and started out in quest of the necessary

capital. He exhausted his private means, and when it

looked as though failure was inevitable Stone &

Webster, of Boston, came to the rescue with a

proposition to finance the undertaking. Of the capital

stock, 35 per cent of it was raised or subscribed in

the United States and the remaining 65 per cent came

from foreign countries, England, France, Germany,

Belgium and Canada being the principal contributors

toward the consummation of a project that had been

hoped for for more than half a century.

On September 15, 1905, the committee in charge of the

affairs of the Keokuk & Hamilton Water Power

Company entered into a contract with Mr. Cooper, by

which the stock and franchise of the company were

turned over to his syndicate, on the condition that

the dam and power plant were to be completed by

February 10, 1915.

A survey of the site of the proposed dam and its

environments disclosed the fact that many acres of the

low lying lands above the dam would be overflowed by

its construction. As rapidly as possible the

representatives of the company visited the owners of

these lands for the purpose of purchasing overflow

rights, and in some instances the lands were bought

outright. Altogether, about thirteen hundred land

owners were dealt with in this way, and it is worthy

of comment that every one surrendered his land or the

right to overflow it without law suits or other

vexatious delays, something unusual where a great

corporation desires private property for some gigantic

enterprise. Fourteen miles of the tracks of the

Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad, that

formerly ran close to the old river bank, were raised

above the new water level, and this also was

accomplished without litigation. At Montrose it was

necessary to remove a cemetery and the company had to

buy a portion of that town, as well as considerable

property at Sandusky and Galland. At Fort Madison it

was discovered that the back-water from the dam would

affect the sewer system and considerable work was done

to overcome this difficulty. Yet all these obstacles

were overcome without serious delays, because

everybody believed in the dam and everybody wanted to

see it built.

In addition to the acquisition of lands or overflow

rights and the changes in the towns above mentioned,

the war department imposed several conditions to which

the plans must conform. Every detail of the

construction work had to be submitted to the secretary

of war and receive his indorsement, really through the

chief of engineers of the army. The building of the

dam made the old Government canal an obsolete

institution. The company was therefore required to

build a lock and dry dock and provide means for their

perpetual operation. Upon the completion of the lock

and dry dock, they were to become the property of the

United States without cost to the Government. Major

Keller, who was in charge for the Government,

afterward stated that the company not only complied

with all the conditions imposed by the war department,

but also did a number of things not included in the

conditions, the cost of which he estimated at

$200,000.

As soon as all these preliminary arrangements could be

completed, work was commenced on the dam itself. To

describe all the details of that work, such as the

building of the huge cofferdam to keep out the water,

the excavating into the bed rock for an anchorage for

the concrete work, the conflicts with storms and

floods to protect the dam during the process of

construction, would require a volume. And while it

might prove interesting to the reader, it is not

considered necessary to give such an account

here.

The length of the dam, including the abutments at each

end, is 4,649 feet, or nearly nine-tenths of a mile.

At the base it is forty- two feet in thickness and at

the top, twenty-nine feet. It is composed of 119

arched spans, so molded together that it is virtually

one solid piece of concrete, which extends downward

about five feet into the bedrock, to which it is

securely anchored. Each of the 119 arches is provided

with a gate of steel truss framework faced with a

sheet of the same metal. These gates can be raised or

lowered and thus keep the water above the dam at a

fixed and uniform level. In times of very high water

they are all left open; in stages of unusually low

water all can be kept closed. By this system a

constant stage of water is maintained above the dam

and the pressure against the whole structure

regulated.

The power house is 1,718 feet long, 132 feet 10 inches

wide, and 177 feet 6 inches high, measuring from the

lowest point in the tail race to the roof. The

foundation begins in the bedrock, about twenty-five

feet below the natural bottom of the river, for the

purpose of gaining more fall. The substructure is one

solid mass of concrete, cast in forms so as to form

the necessary passages and chambers through which

passes the water that moves the great turbines.

Reinforced concrete was used in building the walls of

the superstructure, or power house proper, in which

are the generators, etc.

Between the power house and the Iowa shore is the

lock, which is 1 10 feet wide, 400 feet long, with a

lift of 40 feet. The walls of this lock are 52 feet

high and vary in thickness from 8 to 33 feet. Directly

north of the lock and next to the Iowa shore is the

dry dock, 150 by 463 feet.

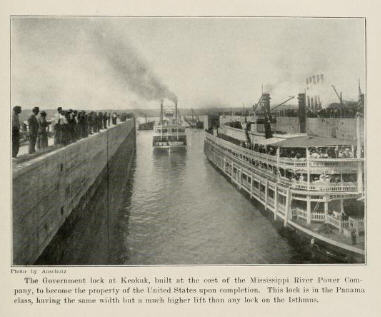

On the last day of May, 1913, the last concrete in the

dam was placed in position. As soon as it set the

water above was gradually raised and flowed through

the spillways for the first time on June 3, 1913. Nine

days later the lock was put into commission by the

passage at one time of two of the largest steamboats

on the Upper Mississippi. On July 1, 1913, electric

current was delivered to St. Louis. The great power

plant was in operation and the dream of years had

become a reality. A formal celebration of the great

achievement was held at Keokuk on August 25, 26, 27

and 28, 19 1 3, the second day of the proceedings

being the day when the great dam was dedicated to the

use of mankind. Governor Clarke, of Iowa, and Governor

Dunne, of Illinois, were prominent participants in the

exercises, and thousands of visitors came to visit and

inspect the work.

The Government lock at Keokuk, built at

the cost of the

Mississippi River Power Company, to become the

property

of the United States upon completion. This lock is

in the Panama class, having the same width but a

much

higher lift than any lock on the Isthmus. Photo

by Anschutz.

Soon after work was commenced the plant was

placed under the management of the Stone & Webster

Management Association, which manages more than fifty

public utilities in all parts of the United States,

and some of their best trained and most experienced

men were sent to Keokuk to look after the service.

Transmission lines have been built to Fort Madison and

Burlington, Iowa; Dallas City, Nauvoo, Warsaw, Quincy

and Alton, Illinois; Hannibal and St. Louis, Missouri,

and light and power are also furnished to the cities

of Keokuk and Hamilton.

The large body of water held in check by the dam,

extending up the Mississippi to the City of

Burlington, has been named Lake Cooper, in honor of

the engineer who designed and constructed the dam.

From the low islands in the river and the partly

submerged woodlands along the shores the timber has

been removed by the power company, so that the trees,

after being killed by the water constantlv standing

around their roots, may not be washed into the stream

and become a menace to navigation. By the raising of

the water level several miles of wagon roads along the

river banks were overflowed. To overcome this

condition of affairs, the company offered to donate a

right-of-way through its property, use its engineers

and equipment and give $75,000 toward the cost of

constructing boulevards to Montrose, Iowa, and Nauvoo,

Illinois. These improvements were finally completed at

a cost of $375,000.

Changing the water level also submerged several

historic points in Lee County. Foremost among these is

probably the huge bowlder known as "Mechanic's Rock,"

from the fact that the steamboat Mechanic was wrecked

by striking it in 1830. This rock is situated at the

head of the rapids, about a mile below the Town of

Montrose and near the Iowa shore. In times of low

water it stood above the surface and was one of the

landmarks used by pilots on the Mississippi. When it

was covered with water boats could take the open

channel without danger. The steamer Illinois was also

wrecked upon this rock on April 20, 1842.

Lemoliese, the French trader who located where

Sandusky now stands in 1820, was buried near the bank

of the river and his grave has been covered by water

since the construction of the dam. Part of the old

Tesson land grant has also been submerged.

Source: History

of

Lee County, Iowa, by Dr. S. W. Moorhead and

Nelson C. Roberts, 1914

|

|