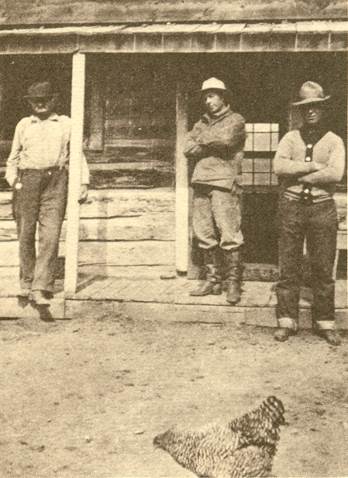

Alex

Alex Cruikshank, Jr., is on the right

Click photo to enlarge

The settlement of

Lee County, Iowa occurred after the vast majority of

Indians had moved westward. Few of the early residents

encountered hostile Indians in their lifetimes.

However, one native of the West Point / Donnellson

area rode west to Montana and Idaho, and was caught up

in the last great Indian war involving Chief Joseph

and his Nez Perce tribe.

--Beginnings--

Alexander Cruikshank, Jr., the son of Alexander and

Keziah Perkins Cruikshank, was born September 12,

1849. His birthplace was a large plank cabin over four

miles west of West Point and over two miles south of

modern-day Pilot Grove. Chief Black Hawk had been a

visitor to the Cruikshank residence before he died in

1838.

When Alex was less than a year old, his father built a

larger home next to the cabin using bricks he made

on-site. It was there Alex was raised, along with

several brothers and sisters. His oldest brother was

the first child born in Lee County, except for

children born at military posts along the Mississippi

River. Little is known of Alex’s early life. However,

he had inherited a pioneering spirit from his father,

who was one of the first settlers of Lee County. At a

relatively young age, Alex moved to Texas, where he

worked for several years as a cowboy.

In 1872, Alex followed his sister, Kate (Mrs. Samuel

Dunlap) to Bannack, in southwestern Montana Territory.

Kate was one of the first public school teachers, if

the not the first, in that state. Alex built a

ranching operation south of Bannack, on Horse Prairie.

The prairie was so named because it was there that

explorers Lewis and Clark bought horses from

Sacagawea’s bother.

--In the Path of

War--

Alex was said to prefer the quiet life at his ranch.

However, during 1877, a year after Custer’s last stand

near Montana’s Little Big Horn River, his property

fell into the path of the Nez Perce tribe that was

alternately fleeing from and fighting the U.S.

Cavalry. The army, under General O.O. Howard, was

under orders to forcibly remove the Nez Perce to a

reservation in Idaho. Chief Joseph led his band of 800

men, women, and children eastward across the Idaho

panhandle into Montana. There they engaged the Army in

the Battle of the Big Hole River. Retreating, they

moved southward along the continental divide.

|

|

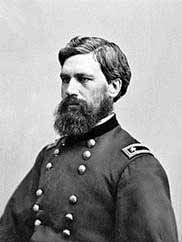

Chief

Joseph

Nez Perce Tribe

|

General

O.

O. Howard

Photo by Matthew Brady

|

Click photo to enlarge

On August 11, the Nez Perce came to the edge of Horse

Prairie and killed four men at the Brenner Ranch. Alex

recalled that “Montague and Flynn were cooking dinner

when the Indians surrounded the house. They put up a

terrific fight, but the Indians over-awed them.

Montague, being shot entirely through, laid down on

the bed where he died. Flynn was found dead lying on

the floor. The house was pretty well shot up.”

“Farnsworth and Winters were coming into the barnyard

with a load of hay,” Cruikshank recalled. “Farnsworth

was shot and killed, but Winters managed to escape

into the brush. Mike Herr, Nobeles [Norris], and

Smith, being in the hayfield, and seeing what was

going on at the house, made for the willows along the

creek, but Smith was killed before reaching the brush,

while the others made their get-away.”

After that encounter, the Indians killed another man

at the Hamilton Ranch, and stole a band of horses at

the Cruikshank Ranch. The cavalry, in close pursuit,

stopped at Alex’s cabin. Because of his familiarity

with the terrain, Alex was asked to serve as a scout

for the soldiers as they searched for the raiding

Indians. He and the other scouts were led by the

veteran, Orlando “Rube” Robbins.

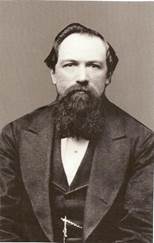

Orlando "Rube" Robbins

Orlando "Rube" Robbins

Click photo to enlarge

--Birch Creek

Massacre--

The Nez Perce, with cavalry in pursuit, crossed the

Beaverhead Mountains into Idaho. Shortly thereafter,

Alex became involved in the so-called Birch Creek

massacre of August 15, 1877. He is perhaps best known

for his recollection of the aftermath of that

incident, one of the most notable of the Nez Perce

conflict. Although he was not an eyewitness to the

massacre, he observed that, “The part I took in this

escapade was more than any other who was at the

scene.”

During their pursuit of the Indians, Alex and his

party were approached by two “Chinamen,” who said they

had just escaped a shootout up ahead at Birch Creek.

Their group of freighters, men who transported

military and merchant supplies, had been captured by a

large contingent of the Nez Perce. Chief Joseph

himself was believed to have been present. The

Chinamen said the Indians had consumed large amounts

of whiskey from the freight wagons and then shot all

the other freighters. The soldiers were asked to ride

to the site and rescue any possible survivors. Colonel

Shoop was concerned that a large force of Indians

might still be there, and that his group was too small

to be an effective fighting force. He started to turn

his soldiers in the opposite direction.

--A Few Good Men--

Alex, however, rode up close to the group and said,

“If there is a man in this crowd that will go with me,

I’ll go to the freighters tonight.” A couple of the

men in the party spoke up. Then Chief Tendoy, a

friendly Bannack Indian, said he and his 15 braves

would also go. It was nearly sundown when they left

Shoop’s party. Alex and his group rode along for about

two miles at a time, and then the Bannacks dismounted

to light their pipes and listen. In time, the group

arrived at the mud flat that was the head of Birch

Creek. They found a nice meadow where they rested

before pushing on to the site of the massacre.

--Confusion in the

Night--

Alex’s recollection: “I fixed my bridle so my horse

could eat grass, but held the reins in my hand and

soon dozed off to sleep, listening to the Indians

(Bannacks) jabbering among themselves. Pretty soon I

heard a sharp whistle at a distance and, raising up to

listen, heard it again but in another direction. I

then fixed my bridle ready for riding. All of the

Indians around me then kept very still, and we heard

the whistle very distinctly in another direction and

heard it answered from a distance. Then we could hear

the sound of the horses’ hoofs going over rocks. We

stayed there quietly for probably 15 minutes before we

started to move on. There was no moon, and it was

pretty dark.”

With stealth, they traveled another ten miles and

heard the sound of horses feeding and dogs barking.

They were close to the reported site of the massacre.

Stopping to listen, Chief Tendoy sent his son ahead to

look for signs of any Nez Perce. Soon a band of

horses, estimated by Alex at 1,000, ran past. Fearing

a sizeable band of Nez Perce would follow, Alex and

his group jumped on their horses and rode away as fast

as they could for several minutes. However, when

things quieted down, they returned to Birch Creek.

By that time, the men had been riding for a long time

without food. Alex said, “We were not looking for dead

men. Grub was what we wanted.” They found the

freighters’ camp fire and grabbed the remains of a

scorched ham and some canned fruit. Then they fell

back into the brush to eat.

Dawn was approaching. A few of the Bannack Indians

reconnoitered the vicinity, and found some horses and

mules, including seven with Alex’s brand. Shortly

thereafter, Colonel Shoop made his appearance with a

contingent of cavalry and some wagons. He said he

would arrange for some Indians to take Alex’s horses

back to his ranch if Alex would stay on as a guide. A

man named Dave Woods then rode up and said he had

found the men who were killed, about a quarter mile

away. Alex threw down his horse shoeing outfit, and

they hurried to the site.

There were indication the freighters had put up a

stubborn fight. The stock of a rifle was on the side

of one man, and the barrel on another. Three other men

were scattered within 25 feet, including one in the

creek bed. Another apparently got away, but was shot

off his horse about a mile away. Alex: “Now there

(were) only five of us to bury the dead, so we dug a

big hole and placed willows in the bottom.”

--Capture of the Nez

Perce--

“I (then) struck out to join (General) Howard’s

command, and caught up with them at Henry’s Lake, and

went through as scout until the Nezperces were

captured.” The chase continued northward, with

periodic skirmishes, through Montana. One of Alex’s

duties as scout was to find meat for the soldiers. He

documented that “as we entered the Judith Basin

(northern Montana), I helped to kill several buffalo

for the army. I killed many of these animals on the

plains, but this was my last buffalo hunt.”

The cavalry finally caught up with the Indians on

September 30, 1877, less than 40 miles from Canada and

safety. The soldiers initiated a sudden charge and

then fell back into a five-day siege during which the

army was able to use its artillery piece. The

conditions were miserable, especially for the Indians

who had no shelter except for brush. Five inches of

new snow fell. By October 5, Chief Joseph realized

their situation was untenable. The soldiers yelled

when they saw a flurry of white rags waving from the

Indian camp. After an exchange of delegations under

truce flags, Joseph sent his famous message to General

Howard, ending with: “I am tired; my heart is sick and

sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no

more forever.”

The Nez Perce lost 43 dead and 67 wounded during the

siege. The army lost 2 officers and 21 enlisted men

killed, and another 43 wounded. Reflecting later on

the fight, Alex wrote that “While I had been so

anxious to get in this fight, yet the sights I

witnessed among the dead and wounded took a great deal

of this notion out of me…It was a horrible and

gruesome sight.”

Chief Joseph lived out much of the rest of his life on

the Colville Reservation in eastern Washington. He has

been featured on at least two U.S. postage stamps.

General Howard later became superintendent of the U.S.

Military Academy at West Point. Rube Robbins spent 25

years as a deputy U.S. marshal and served variously as

traveling guard, work foreman, and warden of the Idaho

State Penitentiary. He also served terms in the Idaho

legislature.

--Prominent Idaho

Rancher--

After the capture of the Nez Perce, Alex went back to

ranching. He followed his sister, Kate, once again

when she moved westward across the Beaverhead

Mountains into the eastern panhandle of Idaho. While

Kate lived in the towns of Junction and Salmon, Alex

found a ranch property at a higher elevation east of

Leadore. He acquired considerable stock interests

there. He was described as one of the few who actually

“rode the range” and “bulldogged the doggies” and

lived the life portrayed by TV westerns. During busy

times, he and his hired men were said to subsist on

sourdough, salt back, coffee, and cold soda biscuits.

Cruikshank’s ranch was fondly referred to as

“Cruikie’s” by the locals. As he was the first rancher

in the vicinity, the valley leading to his ranch

became known as Cruikshank’s Canyon. The creek that

flows through it was called Cruikshank Creek. The

canyon was later renamed Railroad Canyon, but the

creek still bears his name today.

Alex was a bachelor his entire life, and died on

January 25, 1919. He was a pioneer of both Beaverhead

County, Montana, and Lemhi County, Idaho. His obituary

described an openhearted and generous man who gave

lavishly of his own possessions to help his fellow

man. His grave is in Salmon, Idaho.

--Researched and written by John Stuekerjuergen

|

|