| The

stress of World War I AND the Spanish Influenza gripped Johnson County

during the last three months of 1918. Both major events competed for

space in

newspapers. Though the Great War ended in November, young soldiers

would continue to fight the Spanish Influenza War. They continued

to be fatally impacted by the wrath of the disease, both in their camps

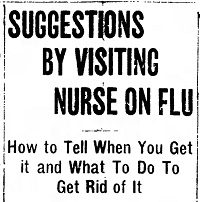

and upon return to their homes in Johnson County. Spanish Influenza undoubtedly existed in Johnson County prior to October 1918. It wasn’t until October, though, when it publicly reared its ugly head. On October 1, the first two “official” influenza cases at the University hospital were reported. Iowa City and the university wasted no time stepping up to address the pending crisis. On Oct 1, Dr. Henry Albert, the Iowa state bacteriologist warned the public: “At

the present time and probably over the next few weeks every case of

cold no matter how mild, should be regarded as a case of influenza.” He

explained, “One reason why influenza spreads so rapidly as it does is

because there are so many mild cases. Therefore, at a time like this

every case of cold should be regarded as a case of influenza. Every

person with a cold should refrain from exposing others to danger. It is

advisable that every such person should remain at home and indeed be

practically isolated from the rest of the family.” He went on to say

“If a person should have a slight cold during the next few weeks and it

is very essential that such person need to look after business away

from home it is advisable to tie a handkerchief or gauze – three layers

thickness – over the nose and mouth. “

There was no doubt the Spanish Flu spread faster than the normal flu. But it wasn’t “the flu” that killed people. Rather, the flu attacked the immune system and then consistently evolved into pneumonia. People died as their lungs filled with fluid. Rural Johnson County witnessed its first influenza related death on October 3 when 37 year old William Floerchinger of Oxford passed away. He died of pneumonia super induced by the flu. Dr. W. M. Rohrbacher was Iowa City’s head health officer on the Board of Health at the time. He had the foresight and wisdom to know that immediate action was needed to save lives in the city. On October 4, he and other city officials entertained the motion of closing all public places. But for reasons unknown, they decided against issuing the order. Instead, Dr. Rohrbacher, along with Dr. Henry Albers and Dr. John Hamilton decided to closely monitor developments over the next eighteen hours. The physicians did, however, publicly insist on the importance of using a handkerchief when coughing or sneezing to prevent throwing germs in to the air and carrying the disease to others. Said Dr. Rohrbacher, “If a person does not observe

this simple precaution he is certainly a slacker.”

The next day, Oct 5, the Iowa City Board of Health took action and communicated it in the manner that most people would see it in those days….the local newspaper. I found it interesting the official order did not make front page news. Rather, it was published on page three. The news article read: “Iowa

City is to be closed up air tight from the hour of the publication of

an order issued this afternoon and printed in this issue of the Daily

Citizen, by the city health authorities for prevention of spread of

influenza. “

The order provided that no theaters, churches, schools, or other places of public gathering were to be open within the city until the order was rescinded by action of the Board of Health. The later clarified the order included private schools. The order also prohibited gathering of children in parks, on the streets or other places. While it’s clear the order intended to stop public congregation, it's interesting to note Father Shulte and Father Shannahan advocated for their morning masses to continue. As the new health order was being publicized, Dr. Rohrbacher made an additional statement to the public: “The

resolution which was passed today by the local board of health, may

seem to some as rather drastic; and it is, the prime object is to curb

this terrible disease influenza; we may not succeed to the extent we

all desire, but that good results will be obtained. I do not feel the

least doubt about. When we consider there are at present some 200,000

cases, with a mortality rate of one in 27, I say it requires drastic

measures to deal with the situation. For this disease is destroying

more lives than Hun bullets. Therefore it is sincerely hoped that the

public will cooperate to the fullest extent. For the success or failure

of the measure depends to a very large extent on the cooperation

received.”

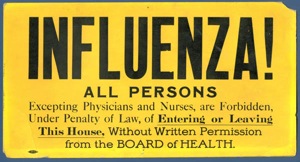

All cases were to be reported to the health department by physicians. As flu cases were reported, infected Iowa City citizens were asked to quarantine themselves in their homes. The homes were then placarded and restrictions were put in place for that site. Police placed the yellow placards on residences to warn others to stay away.

The first official death in Iowa City due to influenza was a seventeen year old university student, Bernard Wallace. The young man died of pneumonia super induced by influenza on Sunday, October 6. Early on, several key physicians were on the front lines, planning the formal attack against the dreaded disease. Most of them worked long hours...juggling the planning meetings with their own patient case loads. In the midst of it all, they too, were stricken. Dr. Hamilton, of the University Bacteriological department; Dr. Koever and H.E. Doden of the University pharmacy department all came down with it at the same time on October 6. By October 10, Dr. W. M. Rohrbacher, who was instrumental in many of the decisions to prevent the spread of the disease in Iowa City and surrounding areas, also became a victim. Miraculously and thankfully, all four pulled through and were able to resume their leadership roles in the fight against the deadly disease. Meanwhile, local physician and surgeon Dr. John G. Mueller was working long hours...day and night...to treat people infected with influenza. He was committed to rescuing people from the wrath of the Spanish Influenza, without giving a thought about himself. Dr. Mueller was caring for sixty cases of influenza when he too, became a flu victim. His illness quickly turned into pneumonia and he was overcome by its cruel wrath. He died on October 17, 1918. In October, thousands of Iowa young men were still being recruited and trained to go to war. However, before they could be trained and equipped to go to battle, many died as a result of contracting the flu in their camp barracks. Others died of the disease, not long after arriving in Europe. The Student Army Training Corps (S.A.T.C.) at Iowa City was hit hard with influenza. Over eleven hundred trainees had contracted the disease. Sadly, there were thirty one deaths. By October 7, the influenza continued to spread at a rapid rate. Hospital authorities reported that about the same number of new cases were reported during the last twenty four hours as in the same time previous or about 125 or more new cases, making approximately 250 cases. Most of the cases were members of the S.A.T.C. so first steps included segregating the men. Two companies of the S.A.T.C. men were quartered on the west side of the river in the new children’s hospital. Tents, arriving out of Des Moines, were set up on the tennis grounds east of the armory to house another 500 – 600 men. A strict military quarantine was put in place about all university buildings but officials announced that the school would remain open. University officials didn’t think the influenza was effecting women as much as men so women were exempt from some of the restrictions. Students were provided with passes and other precautions were put in place. The men were not permitted to go about town. Students were forbidden to leave Iowa City to travel to their homes. Every student who had a cold was required to report it so they could be isolated and treated at Currier Hall, where one wing had been turned into an isolation department. Armed guards paced the sidewalks with fixed bayonets and disputed the way with all who did not hold a pass. On October 8 the following was communicated: "An

order of the Board of Health closed all theatres, schools, churches and

public meetings of all kinds, including the university and intermediate

school but the university proper, coming under military rule falls

outside of the power of the city authorities, it is believed. However,

an order from the commandant decrees that the men of the S.A.T.C. will

no longer be given passes and this has the effect of closing the

university except to the girls and a few others, all of whom must have

passed and be subjected to examination at any time authorities deem it

necessary."

Much to the dismay of avid Iowa sports fans, collegiate games were called off.:

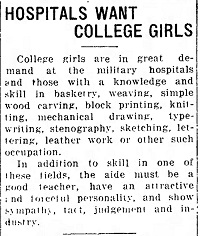

I can’t help but think that people would have incorrectly understood that message to be saying, “All is well”. By mid-October, hospitals had become full and stressed. On October 12 alone, 100 new cases and five deaths had been reported in just 24 hours. Because of the overcrowded condition of the Iowa City hospital, the Iowa City leaders, through the Board of Health and assisted by the Red Cross, established an emergency hospital at the corner of College and Johnson streets. The hospital planned to operate during the term of the epidemic with the capacity of forty patients. University President Jessup stated that 34 physicians at the various hospitals, 180 nurses and 20 army officers were working in an effort to get control of the disease before it had too big of a start. By October 8, an emergency hospital had been prepared at the law building for the care of influenza cases. The hospital occupied the first two floors. University authorities also made preparations to take charge of the Masonic temple to be used as a convalescent hospital for influenza cases. Materials and labor were starting to be in short supply. There was an urgent call in the county for old white cotton cloths at the hospitals. If people had them, they were asked to leave them at the fire station at the City Hall. The demand for assistance at the hospitals was so great that the junior and senior medics were called into the service. Twelve hour shifts and even more, for the doctors and nurses were the rule.

In Johnson County, family and community was everything. Families took care of each other, as well as their neighbors, regardless of the risk of exposure. Mothers traveled to their children’s homes…daughters traveled to their parent’s home…to nurse their ailing loved ones. Sometimes the travel was within the county and sometimes it involved other places both in and out of state. It was not uncommon to see an entire family come down with the flu, including the caretaker who had traveled to be with them. Sadly, multiple members of a single family would become fatal victims of the deadly disease.

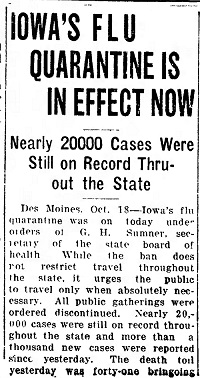

Much to their frustration, local health officials were aware local and rural citizens were not respecting the seriousness of the situation. Peple were continuing to mingle and congregate. To add to the problem, many cases were not being reported. In some cases, entire families were being stricken and were not calling a physician, thus resulting in a formal case not being brought to the attention of the Board of Health. The Board realized that just one of those cases could easily convey the disease to many in one evening at a theatre, one day at school or one hour at church. By mid-October, the State of Iowa Board of Health in Des Moines reported more than 20,000 cases of flu had been reported in Iowa. In response the State Board issued an advisory (not an order) for a thirty day state wide quarantine to check the spread of the influenza. It was just three days later on October 18, however, when the State Board of Health at Des Moines issued an official order to apply throughout Iowa at once, closing all theatres, schools, churches, movies, lodge rooms, and all public gatherings, including public funerals and everything that brought people together in numbers for an indefinite period. Thanks to the wisdom and attentiveness of Iowa City leaders, a similar order had already been in effect, locally, for nearly two weeks. The state order accentuated the city-wide order and the rest of Johnson County fell under the state order. It was confusing to me which parts of the University were subject to Iowa City’s order. A limited quarantine was in effect throughout the university campus. But it wasn’t because of the direction of the Iowa City Board of Health. Dr. Dean, who was Dean of the medical college, and other physicians were under contract with the U.S. government to direct the health measures of the student army training corps. Part of the University fell under Iowa City’s order…the liberal arts and music program, for example. A large part of the University, however, was under the direction of the government. The University had a rough start with influenza but did a great job of getting the situation under control. The University had strict regulations in place three weeks before the State Order was issued. President Jessup felt the campus and students were being carefully and sufficiently guarded. He conferred with and obtained agreement from Dr. G. S. Sumner of Des Moines, of the State Board of Health and with local physicians, to be exempt from the State order. The University then continued with their own containment operation. Dr. Sumner praised the institution for it's excellent control in its handling of the plague. Once the state order came down, all Johnson county residents were now restricted from public gatherings of any kind: no movies, no church, no Sunday school and no public funerals. It included dances and all “functions of every kind that called people together.” Public travel was allowed only when absolutely necessary. Iowa City Mayor F. K. Stebbins communicated, “Now

everything is closed up air tight.”

Despite the orders, Influenza continued to spread mercilessly throughout the county during the month of October. Iowa City was taking a big hit and small rural towns were, as well. On October 21, there were 150 reported cases of influenza in and around the small town of Oxford. Within just one week, that community saw seven deaths. Within hours, the disease took two members of the Lewis family who resided southwest of Oxford on the county line. Lorenzo Lewis, a well-known farmer, died on October 18 after a week's illness of pneumonia, following influenza. Four hours later, his only son, Leroy, aged 20, passed away, also a victim of pneumonia.

On October 24, the State Health Board passed the responsibility of continuing the Quarantine to the local Boards of Health, composed of Mayors and Councils of each town or city or the trustee of the townships. The State Board took that action despite the fact the total number of cases in Iowa was over 35,000. There was a feeling in and around Iowa City the influenza epidemic was on the decline which caused a lot of people to inquire about opening of the city schools. The Iowa City Board of Health consulted with physicians and reviewed all available data. They found flu cases were actually continuing to be reported within the city at an alarming rate. They decided unanimously they would not jeopardize public welfare further by throwing the city wide open at that time. At the same time, the Iowa State Board of Health issued another official order of advice. They recommended: that all public meetings of every kind be called off in those communities where Spanish Influenza existed in any great number and that all people become self-appointed bodies to see to it that everything was done to prevent the serious sickness from spreading more. They also advised to be exceedingly careful for the next few weeks – urging the public to take into consideration the seriousness of the situation and to act accordingly. They advised that where the disease existed, to abstain from public meetings of every kind, from public travel and from visiting from house to house “for this is a time for people to stay in their homes and to keep away from congregations of every kind.” Despite the warnings, people in Johnson County were anxious to get back to their normal routines. It’s uncertain if officials succumbed to the public pressure or if their decisions were driven by data; but by Monday, October 28, rural schools were back in session.

|

Page updated 17 April 2020