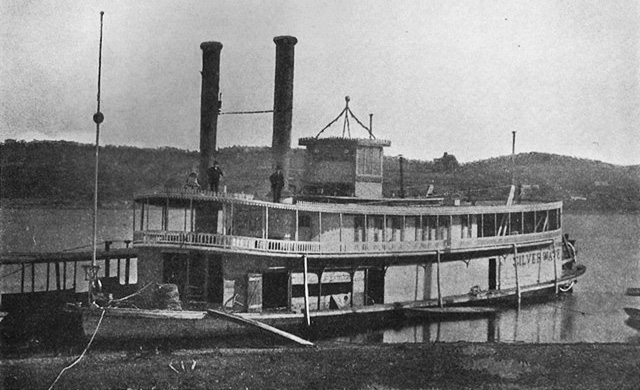

The Noted Raft-boat 'Silver Wave'

95

After we put the 'LeClaire Belle' with her broken shaft in charge of the

Diamond Jo Boat Yard at Eagle Point in November, 1878 I paid off the crew,

and took the boat books and my personal belongings to LeClaire, Iowa

Arriving there on a Friday evening, I left the books at Captain Van Sant's

residence and the next day secured comfortable quarters with a

Mr. Wilson who lived five miles west of LeClaire. On Monday morning I

began a four months' term of school at Browns Corners.

Mr. Wilson was director, as well as my landlord, and had three

daughters (very nice girls) attending my school, so our relations were very

intimate.

Mrs. Wilson was an excellent cook and a very pleasant, jolly woman. I

enjoyed the winter very much. It was an excellent neighborhood. We had

singing schools, spelling matches, debates, parties and dances for our

evening diversion. The winter passed quickly and when school closed the

river was open and and the raft-boats were starting out.

Captain Van Sant placed me on the 'Silver Wave' to fill the same position

I had on the 'LeClaire Belle' in 1878. Captain George Rutherford

was her master and pilot and to my great delight George Tromley, Sr., was on

her as pilot so I could go right on with my pilot-house lessons.

The 'Silver Wave' was a larger and heavier

boat

96

than the 'LeClaire Belle'

and very hard to steer. Like most boats at that time she had two skeg rudders

and only one balance rudder.

About this time someone building a new boat gave her a basket stern with

three balance rudders, and she was such a fine handler that no more skeg

sterns were built and when hauled out for repairs all the old boats had their

skegs removed and were given all balance rudders. When this change was later

made on the 'Silver wave' it helped her greatly both in steering and bucking.

When I joined her early in the spring of 1879, Henry Whitmore of Galena,

Illinois, was chief engineer and James Davenport of LeClaire, his

assistant. Dan Hanley, still living in Davenport was our fireman and his

younger brother, James was cabin-boy and assistant to Joe Gallenor the cook,

where he learned all kinds of mischief and devilment. 'Jimmy' as we

called him then, is now dignified and successful lawyer in Davenport, Iowa,

and he has not lost any of that spirit of devilment that kept the crew of the

'Silver Wave' alternating between fun and fear while he and

Joe Gallenor lost sleep in studying up some new trick or joke to put over on

us.

Mr. Whitmore was not only an excellent engineer, but a fine mechanic.

When a young man he spent four winters in the Broadway Machine Shop in

Saint Louis, learning blacksmithing and machine work and he held the best

jobs in the Galena and Minnesota Packet Company during its successful career.

During the first half of the season I stood

watch with Mr. Davenport and had little to do with Mr. Whitmore as he did not

seem very friendly. During late July and August we laid up three or four

weeks as the

97

Steamer Silver Wave |

| This steamer was originally called the D. A. McDonald. It was built at LeClaire, Iowa, in 1872. Owned by Van Sant and Musser

Transportation Company of Muscatine, Iowa. The author was clerk and nigger-runner, 1879-1881. |

...low water would not permit rafting logs in Beef Slough. To fill in the time

and partly cover the expense, we ran several short excursions. On one of

these, an evening trip, with our boat full of merry dancers, she 'ran through

herself.' That is, she broke the wrist pin on the port crank and this let the

piston head, rod and pitman go forward with such force that

the main cylinder on that side was cracked and ruined. This crash and the

escaping steam caused quite a scare for a few minutes; but we kept them

reasonably quiet and in a very short time Mr. Whitmore disengaged the broken

engine, shut the steam off from it and was able to keep the boat going after

a fashion on one engine and took us back to LeClaire, a little late but all

right.

We had to remove the old engine and get a new cylinder cast by Williams,

White and Company of Moline.

Before the new cylinder was ready, Captain Van Sant received word

that the Chippewa river was rising, that rafting would be resumed in Beef

Slough and to proceed at once to take care of Musser and Company's logs.

When the new cylinder came we worked two days and the intervening night

getting it 'shipped up,' We hardly stopped to eat, and never mentioned sleep

till we had her going up the river going again. After this job Mr Whitmore

wanted on his watch and arranged it so I stood watch with him the rest of

that season and all the next. He took interest in showing me how to do

things. I helped him at the forge and anvil, got to be his favorite striker

and was proud of it. We made all the stirrups for the wheel, and kept all the

mate's raft tools in good shape, and during the summer he made

100

several fine hammers and finished them off as nice as any

store goods.

We said Uncle Henry (as we called him) could make any tools required in

the engine room except monkey wrenches.

In those days there was a great movement of 'harvest hands' northwest,

from Missouri and Kansas to the great wheat field of Minnesota. On one of our

trips we picked up an even hundred of these men at five dollars each for

Winona. This fare was for transportation only. They could sleep on deck

anywhere and get sandwiches and coffee at the kitchen; only a few of them

paid fifty cents for a full meal at the cabin table as they were out to earn

and save money.

At noon the next day when passing Spechts Ferry twelve miles above

Dubuque, our main hog chain on the port side let go on top of the after main

brace. This let her stern down on the side and put wheel, cranks, pitmans and

engines in such a twist we could not roll the water wheel over.

The pilot headed her for the shore, her headway carried her there and the

mate and crew got lines out to hold her.

Captain Sam Van Sant was riding up with us this trip fearing we might have

some trouble with so many deck passengers.

When the boat was tied up he came back to see the situation at out end

and he looked pretty blue.

Speaking to the engineer, he said, "Well, I guess the only thing to do

is to send these men to Winona by rail and then have the boat towed to

Dubuque Ways for repairs."

Mr. Whitmore said, "Captain, you do what I direct and give me some help

and I'll see what we can do."

101

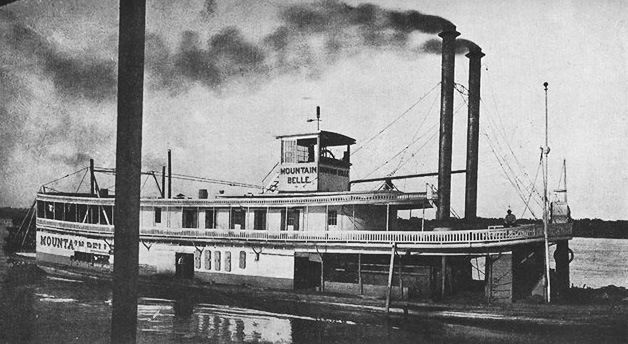

Steamer Mountain Blue |

| Originally a packet on the Kanawha river. Was brought him into the

rafting business in 1874 by Hewitt and Wood of LaCrosse, Wis. She was later owned by G. C. Hixson and then for several years by McDonald Brothers of LaCrouse. Her last years were spent in the excursion business at Saint Paul and Wm. McCraney as master and owner under the name of the Purchase. She had a long and successful career, and was finally condemned and dismantled by Peters and Son at Wabasha, 1917. She never had a bad mishap causing any great loss. |

103

The iron where it had broken was five inches wide and three-quarters

thick and it was a clean job to weld it with our little outfit.

It was awfully hot, close in under the bluffs that afternoon, but

before the supper bell rang we had her stern back up to place and the chain

with that weld held her until she was dismantled many years later.

We had no trouble with our passengers and they made better time with us

than if they had taken a regular packet that made frequent stops and

handled considerable freight, and the five hundred dollars passage money

they paid added just that much to the net profit of the trip.

Nearly all our work was running log rafts from Beef Slough, Wisconsin,

to the Musser Lumber Company, Muscatine, Iowa, that owned a half interest in

the 'Silver Wave.'

About this time the Musser Lumber Company and Captain Van Sant

incorporated the 'Van Sant and Musser Transportation Company' that

continued to the end of the rafting business.

I remained with the 'Silver Wave' three full seasons; two of them with

Captain George Rutherford and one (1881) with Captain Lome Short who gave me

great encouragement and opportunity to practice on the river and before the

season was over he would let me 'take her' anywhere night or day and

fortunately I kept her out of trouble and made life easier for him.

We had very high water in the fall of 1881 and

some landings were hard to make. On the trip we had a raft for the Clinton

Lumber Company. At Dubuque I got orders from them to bring the raft 'to our

mill.' Captain Short knowing the landing to be swift in high water had

everybody up, skiffs and check lines ready

104

and the engineer had a clean fire and plenty of steam.

We got it landed at the mill all right early in the morning. Then the

superintendent, Harry McGlynn, came down in ill humor and refused to receive

the raft there; said they could not hold it, wanted it up above in

Joyce's Slough and wanted to know "why in h--1 we didn't put it there,'"

"Because your letter we got at Dubuque told us to bring it to the mill."

He said, "yes, but I wired you last night in care of the Sabula bridge to

put it in Joyce's Slough." "Well, we did not get your telegram. Don't know

why, but through no fault of ours the raft is here and we can't take it back

up the river and don't intend to try, so here we are."

I went up-town and consulted a good, sensible lawyer, then returned to

the Lumber Company's office and we compromised. They gave me a clear receipt

in full for the raft 'Where is as is.' Then we agreed to leave our kit on and

assist the steam 'Chancy Lamb' and 'Lafayette Lamb' in putting the raft up

in Joyce's Slough.

Taking one-half at a time and using all three boats we soon had both

pieces up where they wanted them, when they put on their lines and we took

ours off.

We were all done and coaled up ready to start back up the river before

dark and everybody was in good humor.

That lawyer charged me three dollars for his advice. It was a good

investment.

Before leaving Clinton that evening we got a

newspaper account of the accident of the little steamer 'Jennie Gilchrist'

the night before. The western Union Railway was under water between Hampton

and Moline. The 'Jennie Gilchrist' made a few trips carrying freight and

passengers, while this condition existed,

105

and left Davenport about 8:30 P.M. with a few passengers and some freight on a

barge. She passed up through the government bridge all right,

but when about up to the location of the old railroad bridge she had a

breakdown on one engine and before the engineer could get her cleared

up to work the other engine alone she drifted down to the government

bridge, her upper works caught and she capsized. Some of the people

were saved by getting on the barge and others were rescued by skiffs

from shore, but there were some loss of life.

The 'Jennie' was raised. repaired and had a long and useful career after

this accident.

The 'J.S. Keator' of Moline, Illinois, broke her shaft later in the season.

We had finisher our regular work and were ready to lay up for

winter when we received orders to go to Gordon's bay for a raft that the

'J.S. Keator' was going for when she broke down. The water was high,

the weather nice and the 'Silver Wave' made a quick and very profitable trip,

the last in 1881.

The winters of 1881 and 1882 were my last experiences in teaching; my

fourth in the same school at Brownes Corners. I had grown to know and like

everybody in the neighborhood. They were very kind to me and I had become so

attached to the scholars that I left in the spring with genuine

regret.

In addition to the many boat stores where we purchased supplies there was

a well conducted wharf-boat at Bellevue, Iowa, that carried a good

stock of boat supplies. It was in charge of a fine old man named Peter

Shiplor who had been a clerk on the packets and knew how to cater to

the steamboat trade.

It was handy to land at

going up river as we could

106

get ice, meat, and

provisions aboard in a very short time and Mr. Shiplor always had our mail

ready for us.

Going down the river we would always pull ahead in the skiff and tie up to

the wharf-boat, load in our supplies and be ready to pull out to our

steamer as she was towing by the town.

In 1880 there was an epidemic of small pox in Bellevue but we had not

heard much of it while up river and on our way down I went ahead as usual

with our skiff and got needed supplies.

It was nearly six o'clock when I got back to the boat. After I saw the

stuff taken out of the boat and properly put away I went upstairs and took my

seat at the supper table with the captain, engineer, mate and watchman.

Someone inquired if there was any truth in the rumors about small pox

epidemic in Bellevue.

I told them I knew all about it. That Ben Stuckey the watchman of the

wharf-boat had had it and was now nursing others who were sick with it.

That Big Jake the colored man who did the hauling for the wharf-boat,

was very bad with it. They did not think he would live through the night.

That Mr. Shiplor was having a hard time running the wharf-boat as no one

would come to work with him. That it was pretty bad up town. There had been

several deaths recently and a good new cases. But I found myself alone at the

table before I finished my story. I don't remember just what

they did call me, but when the cabin-boy heard what I said he ran back to

tell the cook and as a result I got no more waiting on and the other 'watch'

would not come to supper until I had left the table.

Then to make matters worse, we tied up two

miles below Bellevue under a high bank and cooled down for

107

all night to clean boilers.

After 9:30 P.M. all the crew except myself were in bed and asleep. I had

to stand watch until midnight and then call my partner who would watch until

breakfast.

I soon wrote up the log book, recorded a few bills paid that day and

balanced my cash. It was very quiet and I soon got sleepy as I had missed my

usual afternoon nap on account of business at Dubuque and Bellevue. To keep

awake I got up and walked decks. About 11 P.M. I saw several lights

coming down the road around the bend above us from the direction of Bellevue.

A little later I could hear several voices back up on the high

bank but they were not close enough to make out what they said. My curiosity

was aroused and as the voices continued I cautiously walked the logs, got

ashore and found a place where I could climb the high bank and found myself

in a cemetery close to the party burying the latest victim

of the small pox, Big Jake, the colored teamster from the wharf-boat.

When I roused my partner at midnight and got him up we had our lunch

and casually I mentioned the affair I had witnessed in the cemetery and

remarked " There may be another before morning. If you see lights and hear

voices up there, you'll what's doing.." I said," You knew Big Jake didn't

you, Jim?" "Yes, and I don't want to hear any more about him."

I suggested that perhaps it would be just as well not to mention the

funeral to the crew when he called them at three o'clock to wash boilers and

pumps up, but when I got up for breakfast I found they knew it all

and some were in favor of putting me ashore. Of course they couldn't do that,

but I had my breakfast alone and no one wanted my company that day.

108

On long trips we received little mail and few papers. Only a few

'Firebox Reports' [Unconfirmed Steamboat news attributed to firemen] and 'Cook House' [Unconfirmed Steamboat news attributed to the cooks] dispatches were in circulation to kill the monotony.

Sometimes we made the run from Beef Slough to Muscatine without landing.

After delivering our raft at Muscatine or elsewhere we got our kit off the

raft and stowed on the boat and aside from stopping at LeClaire (usually) for

coal we raced all the way back to Beef Slough with-out landing.

The 'Silver Wave' could run well when she was in good trim. She needed

a good load on her head. On one trip she ran from LeClaire to Beef Slough

in twenty-nine hours and thirty0seven minutes. The distance is three hundred

miles. This run has not been beaten by any raft-boat to my knowledge.

There was considerable racing with other boats in those days. Mr. Whitmore

was always proud of his boat and did not want her passed.

If someone reported a 'smoke ahead' he always got busy and wanted to get

close enough to read the name even if he could not pass her.

The prevailing opinion is that racing on the river is dangerous. The

movies generally show an explosion of boilers as a natural feature of a

steamboat race. This is all wrong. The safest time to be on a boat is in

a race.

The engineer, firemen, mate, and watchman are

awake and alert on the main deck. The pilot is taking pains to do his very

best steering, the captain is in the pilot-house or close by to give any

needed assistance and the rest of the crew even to the 'slush cook' are

inter-

109

ested and ready to

'trim ship' or do anything else to help their boat win.

I have never known a boat to explode her boilers or have any serious

accident while racing.

There have been a few explosions - not while racing - that could only be

accounted for by the facts that engineers do sometimes get tired and

sleepy and when conditions and tired are too harmonious they do go asleep

and the water in the boilers gets too low.

Steamboat boilers must be built according to United States laws, of the

very best material and subjected to very rigid tests by the United States

inspection service before they can be used. They must stand a cold water

test one hundred and fifty percent of the steam pressure then allowed.

A set of boilers to carry one hundred and eighty pounds steam pressure must

stand two hundred and seventy pounds water pressure test, and this test is

applied at least once a year as long as they are in use.

If I thought boiler explosions a mystery I could not have slept so comfortably over them for fifty years.

Search lights or electric lights had not come into use during the time

I was learning the river. We had kerosene lamps and lanterns for lighting

and the only thing we had to help the pilots landing at a bad place or

hitching into the raft at night was the miserable old 'torch basket.' This

was an iron basket about the size and shape of a ten-quart pail, that was

hung on the end of five foot iron handle.

Using dry pine kindling cut up fine to get a good start we fed the torch

with crushed resin a little at a time and then occasionally more wood.

This made a lot of smoke and some of the time a

110

pretty fair light, but it required close attention and at best was generally criticized by the captain and pilot on watch.

The watchmen were expected to have a barrel of kindling and a bucket of

resin always ready so we could flame up the torch on short notice.

This would have been easy enough but for the cooks who frequently

stole our stock to start or hurry up the fire in their big range.

After running two or three nights without landing, perhaps just as the

watchman was nearly ready to turn in the whistle would blow for a wood pile

and the 'skipper' would call for the torch.

Rushing down to start it, it was no uncommon thing to find the kindling

barrel empty and the resin pail nearly so. Frequently we would find part of

the kindling and some of the resin behind the kitchen range. Of course when

the cooks got up at 4: 30 A.M. and discovered their supply (stolen from our

stock) had vanished they made the air blue with all kinds of swearing and

threats and tried to pin the whole thing on the watchman.

That torch was the one serious bugbear that made many nights miserable.

After electric lights were installed the watchman led a different life.

During the three seasons I spent on the 'Silver Belle' we only had one bad

break-up.

Captain Rutherford tried to run Cassville Slough with the whole raft in

the night and without any searchlight. Captain Van Sant was aboard that trip. He

advised against trying to run it 'whole.' He urged Captain Rutherford to tie

up and wait for the daylight, but Captain Rutherford was always ambitious to

make

111

time and kept on. We made the bends and other places all right but came to grief at the head of

the island nearly at the foot of the Slough, one corner caught on

the island and the opposite corner on the stern caught the bar on the right

and before we got the wreck landed in the last right hand bend at least

one-fourth of our raft was floating off down the river. Then a dense fog

settled down on us that did not lift until nine o'clock next morning.

By this time the mate had 'the remains' patched in good shape so the steamboat could handle backing, floating, or towing along slow.

We had three skiff crews out catching and collecting the loose logs,

many of which grounded on shallow places and had to be rolled to deeper

water.

Leaving my partner to stand my watch running the nigger engine, I went

with Captain Van Sant in one skiff. We had with us a big, husky negro who was

riding down river with us. We soon had him in the water with a peavey and he

did excellent work rolling off logs that were aground while we caught and

brailed them together and towed them out to the raft when it came along. The

day was warm and calm, a line day for our purpose, and we cleaned up every

log in sight as we went along.

We had no dinner, and it was 9:00 P.M. when the boat landed and we all

gathered in.

Joe Gallenor had a fine supper for us and we certainly enjoyed it and the sleep

afterward. I don't know who stood my watch that night, I was far away on the

billow. The next morning we started out again but we had secured the bulk of

our logs the first day. We rowed

112

and floated along catching a stray now and then, the last one in Bellevue

Slough, fifty-five miles from where the break-up occurred.

We had 1200 logs scattered over fifty-five miles of river. We recovered

them all and delivered at Muscatine without any shortage and

only one day late.

Captain Van Sant's presence was a great help to us in many ways. He knew

what to do and had the happy faculty of knowing where to place each

man in the right place and get the most work out of him. He earned the title

cheerfully given him by the men on deck when they pronounced him

'A Hero in a Break-up.'

Captain Rutherford was on the 'Silver Belle' six seasons and she made a

lot of money in that time. He was not only an excellent pilot, but a man of

intelligence and good principle.

One evening during a discussion in the pilot house something said prompted

him to face me and placing a hand on each of my shoulders he

said, "Young man, remember this:

Life lays its burden on every man's shoulder,

We each have a cross or a trial to bear,

If we miss it in youth it will come when we are older

And fit us a close as the garments we wear. I thanked him and asked if he knew the author of his beautiful verse. He

did not, nor do I.

We made one long, tedious trip with a raft of

lumber from Reading's Landing to Hannibal, in September and October, 1879.

The river was very low and Beef Slough had closed down. We took this raft on

charter, so much per day, which assured us of a fair profit. We grounded raft

and boat at the mouth of Skunk river, seven miles below Burlington. By two

days hard work

113

we got off in pieces.

Then we lost two more days by wind, before getting away from this place.

It was slow, hard work putting the raft through the canal as we had to cut

it up in small pieces at each of the three locks in the old canal around the

Lower or Des Moines rapids which ended in Keokuk.

We were twenty-eight days on the trip but after all our delays and mishaps

I got a clear receipt for the raft from the agent of the Eau Claire Lumber

Company when we turned it over to their steamer 'Pete Kirns'

at Hannibal. In fact he complimented us on the good comdition of the raft

and the time we had we had with it.

As our pilots had not been running below Muscatine for a few years they

sent me ahead to Davenport to secure a 'posted pilot' to go down with us and

show them the way.

Several of the large Saint Louis and Saint Paul packets had been laid up

on account of the low stages of water and I was fortunate in getting David

LeClaire who had been on the 'Belle of LaCrosse' and was well posted. 'Dave'

LeClaire , then a very strong, healthy man about sixty-five years old, was a

half-brother of Antoine LeClaire, the founder of Davenport, Iowa. I found him

very intelligent and sociable. I enjoyed his company very much and told him

so when he left us on our return to Davenport. That was Dave LeClaire's last

trip. A few mornings after when his wife called him, he did not answer. He

had made his last 'crossing' to the other shore.

Racing between raft-boats going up the river (usually without anything in

tow) was very common, but it was always interesting and often exciting

though there was nothing at stake, except the pride of the crews in their

respective boats.

114

Captain Van Sant was justly proud of the speed of the 'Silver Wave' and

the 'Musser.'

After we bought the 'Ten Broeck' I soon discovered that when loaded

just right she made excellent time going up river, but she would not stand

crowding when heavily loaded as she did not have much free-board forward.

One night on backing out from a wood pile near Fisher's landing to go back

up to Beef Slough for our second piece, I saw a boat coming up

behind us and apparently gaining on us. I called down to James Stedman,

the chief engineer, who was on watch, telling him we should try to keep ahead

until we got up to the boom ( about eight miles). By the time he and the

fireman got a good fire and our usual steam, the other boat got up close, her

bow even with our wheel and we saw she was the 'Musser.' Her

pilot whistled to go by on the right but he did not go by. I kept well to my

side of the channel, the 'Ten Broeck' got her gait and gradually increased

the gap between us and went into the mouth of Beef slough four

lengths ahead.

I warned our crew not to mention anything about it as the 'Musser' may not

have been in as good trim as the 'Ten Broeck."

Now comes the funny part of it. On our next trip coming up we had a very

heavy load of fuel and iron boom chains on the 'Ten Broeck' when we landed at

Winona and Captain Van Sant came on to ride up to Beef Slough with us.

While eating supper at the Winona dock the captain gave me and the

engineer a very kind but serious talk about racing and he would admit

he had done a lot of it in his time, but could plainly see now that there

was no sense in it , etc., etc.

115

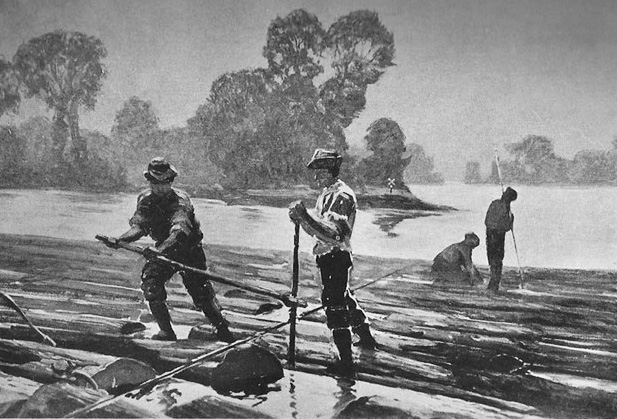

Tightening Crosslines with Spanish Windlass |

| The lines holding the raft together and keeping it straight had to be frequently tightened in the manner shown. The Spanish Windlass consisted of two light poles about four inches through as the butt ends. One called the

'upright,' about six feet long, was fairly held in a vertical position by one man while another man carried about the ten-foot pole called the

'sweep.' The hitch caught in the bight of the loose line could in this way be wound around the upright until a good strain was secured and, held by the windlass, laid down flat. |

117

We promised to remember his good advise. When we reached the upper

end of town the new, fast 'City of Winona' came out of the foot of the

Slough above Yeoman's mill and was soon headed up for the Beef Slough.

She was gaining a little on us. Captain Sam was eagerly watching and soon

asked Mr. Stedman, the engineer, how much steam he was carrying.

I answered, saying, "I have given orders not to carry over one hundred and

twenty pounds tonight. Until we get these chains off her head, she will dive

when she strikes a deep place if we drive her any."

By this time the 'Winona' was close up to our wheel and gaining a little.

Captain Sam could not stand it any longer. He said to Mr. Stedman and me-"Why

this is fast boat. It's a shame to hold her back this way. let steam come up

to her allowance and I will try to keep the water off her head";

and he got the crew to help him move some chain back; then he banked coils of

cross lines around her bow with tarpaulins over her head and we kept ahead

and gained a little even with slowing her down to mount the reefs in shallow

water; but when near Fountain City the water came over

her bow so strong that captain Sam and his false bulkhead were washed back

off her head. We then concluded we had had fun enough, slowed down, let the

'Winona' go by , then cleared up the forecastle, put but her back on one

hundred and twenty pounds and turned in. 'Racing' was not

discussed when the captain came aboard after that.

Sometimes, however we raced down stream with rafts in tow. I remember one

such when on the 'LeClaire Belle' in 1878.

We had fourteen strings of logs for fort Madison. The 'J.W. Van

Sant' (first ) with fourteen strings of

118

lumber for Saint Louis, was close

behind us when we got coupled up below the Clinton Bridge, and it was soon

apparent that she was gaining on us.

As the water was at a low stage and only one rapids boat, the 'Prescott,'

at LeClaire to assist over the rapids, each captain wanted to reach LeClaire

first and go on over with the 'Prescott's' aid, as the second arrival would

have a long delay.

The 'LeClaire Belle' had fourteen-inch cylinders and the 'Van Sant' only

twelve-inch both had the same stroke- four-foot. Not only did the 'Belle'

twenty percent more power, but she was a much larger boat and we made every

effort to to keep ahead. by the time we were at Camanche we were

we were side by each. And a few times the crews had to pry our boom logs

loose from the lumber. Both boats were doing their best and so were their

pilots, but there was no swearing or calling of ugly names- it was all quiet

and orderly as a well conducted funeral. That stretch of river then was wide

enough for two full rafts to run abreast all the way to LeClaire. Neither

crowded the other on shore or out on a bar; it was a fair test in

every way and we were loser. it took over an hour before the 'Van Sants'

raft cleared ours at the head of Steamboat Slough. When we reached

the LeClaire Foundry the "Van Sant' and the 'Prescott' were starting over the

rapids. We had to land and wait until the next day at noon.

While a lumber raft has more feet in it and weighs more than a log

raft of the same length and width, it is easier to tow, because it is of

uniform depth and the cribs and strings are coupled up close together,

while the logs being of different sizes, the bottom of a log raft is very

uneven and rough.

It takes longer to get a lumber raft under way

or to

119

check its headway and stop it, but once under way the same boat or one of

equal power, will shove fourteen strings of lumber one-fourth to one-half

a mile an hour faster than she will fourteen strings of logs. In calm weather

a lumber raft will float a little faster than one of logs.

The usual speed of a standard sized raft towed by a boat of average power

was four miles an hour except in Lake Pepin or Saint Croix where it was only

two and one-half miles an hour. The speed was considerably affected by the

stages of water and the force and direction of the wind.

A pilots reputation depended almost entirely on the time in which he made

is trips, and there was constant effort to get all the speed possible

and to lose as little time as possible at the bridges or at the rapids. The

owners of the boats did not have to urge their pilots to 'make time'; the

rivalry between the pilots kept them all doing their best. It was racing

against time and each other all season.

The engineers and mates deserved a large part the credit for the good time

made, but the captain, who was also first pilot, got the lion's share

of it while the others got their full share of the blame if the boat lost any

time, or was a little longer than usual on her trips. The rivalry between

captains in the same line or on boats, owned by the same company, was

sometimes bitter.