|

Col. Thomas M. Seymour

Pictorial

Memories

Born in Dubuque on Sept. 27, 1916, Tom had

his early education at St. Anthony’s School and then attended Loras

Academy from where he graduated in 1934. Four years later he

completed his college course at Loras College and received his

Bachelor of Science degree with a mathematics major and a physics

minor. He attended CMTC Camp Des Moines, Ia., for four summers, and

was commissioned a second lieutenant in the reserve in 1936 just

after completing his second year of college. At Loras College,

Tom was a member of the vested choir for four years, on the staffs

of the Spokesman and The Loran, and played in the band.

On July 11, 1939, he enlisted in the

Army Air Forces at Des Moines, Ia., and was sent to Spartan

Aeronautical School, Tulsa, Okla., for a three months course.

Following completion of this, he was transferred to Randolph Field,

Tex., and from there to Kelly Field, Tex., where on March 23, 1940,

he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the regular Army and

awarded his fighter pilots wings.

For three months following his graduation,

Tom served as an instructor at Kelly Field, and then was sent to

Mitchell Field, FL. for two months instruction on the two motored

bomber school located there. In November 1940 he completed his

course as a bomber pilot, and was transferred to Langley Field, Va.

for four months further study.

An article in the Telegraph Herald

described one of Tom’s missions:

|

|

|

Dubuquer Aided Hunt

For Lost CAF Plane

Lieut. Seymour Flew One of 9 Bombers Sent to Canada

The dramatic search by U. S. Army bombers

for six Royal Canadian Air Force fliers, who bailed out of

their Atlantic Patrol plane just before it crashed in the

desolate bush country near East Lake, Quebec, Nov. 17, was

described in letters received here from Lieutenant Thomas M.

Seymour, of Dubuque, who aided in the hunt.

The son of Mr. and Mrs. Victor F, Seymour, of 1710 Asbury

Street, Lieutenant Seymour piloted one of nine U. S. Army

Douglas bombers that scoured the rugged terrain under

difficult flying conditions in search of the missing men.

Three Still Missing

Three were found and three are still missing.

It was the U. S. plane in which Major H.

L. George, commander of the American squadron, was riding,

that caught the first glimpse of the wreckage of the Canadian

plane just inside the United States. A member of the plane’s

crew saw the marked tail of the crashed plane, but so dense

was the forest and underbrush that the Americans could not

confirm the fact that the wreckage was below for another 20

minutes.

“In order to obtain a sufficiently clear view of the terrain

it was necessary to fly very low so that the propellor blast

of the searching plane would blow aside the tree tops,

permitting a view of the ground,” according to a story of the

search received here from Lieutenant Seymour.

Long Flights Made

Lieutenant Seymour was one of 4 officers

and crew members who flew to Canada from Langley Field, Va.,

in nine bombers to join in the search at the request of the

Canadian government.

The squadron was grounded the first day by low ceiling and

scattered snowfalls, but on the second day Lieutenant Seymour

covered 300 square miles in his plane. Similar long flights

were made during the next two days.

Canadian newspapers said one of the squadron narrowly averted

a crash Nov. 22, just before returning to the airport at

Montreal. Following a valley in the East Lake area, and flying

close to the ground, the man at the controls took a sharp turn

to the right. Suddenly the valley ended and a steep climb was

necessary to avoid hitting a hill.

One of the officers was quoted as saying: “For a moment, it

seemed that the hill was gaining altitude faster than the

plane.”

“Million Parachutes”

The difficulty of spotting a parachute

was very great “With the snow on the tops of the fir trees, it

seems as if there are a million parachutes down there,” one of

the pilots remarked.

The Canadians were forced to jump from

their big Digby bomber when they ran out of gas and iced up

badly, just inside the Maine border. The crew jettisoned the

plane’s load of bombs over desolate woodlands before they

jumped.

Lieutenant Seymour’s last letter from

Montreal said hope for the three men still missing had

virtually been abandoned. |

In March 1941, Tom was sent to the Jackson, Miss., Army Air Base,

where he was stationed as an instructor and operations officer until

December, 1941, when he was transferred to San Francisco, Calif., to

go overseas. His orders were changed, however, and after three

months in California, he was transferred to Wright Field, Dayton,

Oh., where he served as test pilot on B-26’s for three months. From

Wright Field, he went to Barksdale Field, La., where until January

1943, he served as group operations officer. From Barksdale Field,

Tom was promoted to Major and sent to MacDill Field, Tampa, Florida.

There he joined the 387th Bombardment Group (M) with its four member

squadrons, the 556th, 557th, 558th and 559th as group S-3.

Col. Harry Dennis (Ret) was a

2nd Lt. Bombadier in the 387th and he offered this recollection:

“Met Maj. “Whip” Seymour early in January of 1942 at MacDill Army

Air Field, Tampa, FLA new Bomb Group was in the process of

activation to be designated as the 387th Bomb Grp (M) B-26 Martin

Maruader. The Group Commander, Col. Carl Storrie had appointed

Major Seymour Group Operation Officer and in the process challenged

him a low altitude skip Bombing Competition to take place on Avon

Park FL. Bombing and Gunnery range.

My role was bombardier for Col. Storrie while a

former Bombardier in the RAF (tranferred to AAF) was to fly with

Whip Seymour. Col Storrie and I emerged as winner with the lowest

CEP (circular error) out of ten practice bombs each and the winner

of a bottle of good whiskey as well. The scoring personnel on the

range reported they had never seen such spectacular flying by both

pilots”.

~~~ *** ~~~

Europe

The 387th was named the “Tiger Stripe Marauder Group” due to the

slanted yellow stripes painted on the vertical stabilizers of the

planes. The men and planes arrived in England in July 1943.

Some of the missions that Col. Tom was involved

in were described in a history of the 387th “Two noteworthy

missions were flown in November (1943) against a new type target -

the ‘noball’.

“These objectives consisted of rocket guns and

‘pilotless’ aircraft installations in the Pas de Calais area of

France. The installations had a two-fold handicap for the

bombardiers: (1) Because of their comparatively small area and

expert camouflage, they were very difficult to spot from the air,

especially if the weather was hazy; (2) Because of the small area

covered, they were extremely hard to hit. They required excellent

‘pinpoint’ bombing. The first noball target hit by the 387th was

Vineyesques, France near Cape Gris Nes on November 5. The second was

against Martinvast in the Cherbourg area on November 11. Results

were fair to good. The ‘noballs’ offered a real challenge to

pilot-navigator-bombardier crews in teamwork and coordination.

Bombing accuracy steadily improved; and after the invasion forces

had landed on the continent, results could be evaluated. Mediums,

again, had proved the effectiveness of ‘pinpoint’ bombing technique.

“On November 3 the group achieved its best bombing results up to

that date. With good visibility and little flak, the formation, led

by Lieutenant Colonel Seymour and Lieutenant William Tuill, hit the

airdrome at St. Andre de L’Fure with excellent results. The aiming

point was a group of repair shops and living quarters. Of the

forty-five buildings in the area thirty-six were destroyed and

several more damaged by the concentration of bombs that fell in

perfect pattern. Four planes were damaged by flak. The aiming point

was a group of repair shops and living quarters. Of the forty-five

buildings in the area thirty-six were destroyed and several more

damaged by the concentration of bombs that fell in perfect pattern.

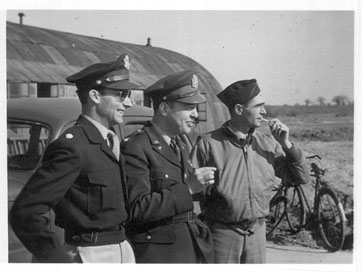

Three Group Commanders:

Seymour-Brown-Caldwell

|

“With only fifteen operational days during April the group achieved

excellent bombing results. Targets included ‘noballs’,

marshalling yards, and for the first time since September, a number

of coastal defenses. The first of these occurred on April 10 when

Colonel Caldwell led a thirty-six ship formation over Le Harve. The

bombardiers had not lost their accuracy; for all strikes were seen

to hit the target area, and one scored a direct hit on a gun

emplacement. The same afternoon Lieutenant Colonel Seymour led the

attack on the Namur marshalling yards. Following a formation of

‘window’ ships, the 387th dropped incendiaries which started

numerous fires.

“The joy crews felt after the two highly successful

missions of the 10th was short-lived. Two days later, leading a

formation over coastal defenses near Dunkerque, Colonel Caldwell and

his crew were shot down by enemy flak….

|

Colonel Caldwell was

succeeded as commanding officer by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas M.

Seymour, who had been with the 387th since MacDill Field.”

Bill Redmond kept a diary against regulations and here is one

excerpt:

“Mission #56 – May 24, 1944: In the

afternoon we went after 6 – 88mm naval guns north of Le Touquet. We

bombed in 6’s. 1st 6 hit military installations north of guns. 2nd

(our high flight) hit 2 guns and disabled 3rd gun. 3rd 6 poor and 2

other flights got fair results. Col. Seymour rode as our co-pilot.

No flak.”

|

|

|

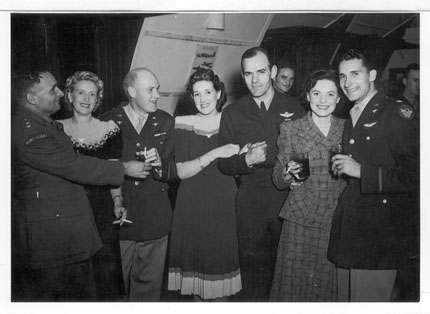

“…On

the social side the various squadrons staged several enjoyable

parties. Accommodations at the field were being improved, and

the presence of English girls and American nurses continued to

be a welcome change. A decided uplift in the morale of the

combat crews at this time was felt by the return to the United

States of several veteran combat teams for well deserved

rests.” |

Lt. Col. Seymour (far right) at

the Officer's Club with some English Girls

(Col. Storrie is far left) |

Col. Gayle L. Smith recalls

his association with Col. Tom and he shared them in a letter to me.

Smith was born on a farm near Arlington, Iowa and graduated from

Upper Iowa University where he majored in Math and participated in

baseball, basketball, football and band and orchestra.

“Our mission in combat was to attack missile

sites, coastal fortifications, military air fields, anti aircraft

installations, ammo and fuel supply points, transportation

facilities, research and manufacturing facilities and after the

invasion assist our army by denying access on escape by destroying

roads, bridges, and railheads. In other words prevent the enemy from

advancing as well as retreating to regroup.

| |

|

|

“..Col. Thomas

Seymour. He was the Group Operations Officer for a B-26

training group at Barksdale Field, Shreveport, LA. when I

first met him. He was a Major then (Aug. 42) and was

responsible for establishing and monitoring combat crew

training in the B-26 Martin Marauder. In this position he had

already established himself as an excellent pilot in the B-26

and was highly regarded as an authority in its operation. My

contact with him, as a 1st Lt., was in the capacity of an

assistant Squadron Operations Officer and an instructor pilot.

I would have meetings with him a couple times a week until

late Jan. 43. At that time we both received orders to

|

report to the 387th Bomb Group-a unit that was in the early stages

of formation for overseas. His orders specified his assignment as

S-3, Group Operations Officer-my order specified as Asst. Group

Operations Officer. (I have often wondered as to whether he was

instrumental in selecting me or not. He never said and I never

asked) I don’t know if Tom knew I was from Iowa or not. He would

have access to my records when I would not have access to his. A

discussion of our backgrounds never took place.

“Now in our new jobs, I worked

directly for him from Feb. 43 until 17 April 44 at which time he

elevated to be Commander of the 387th.

“In his position of Group Operations

Officer he was responsible for organizing all of our combat

missions, ie. crew briefing, airplane formations, routes to target,

assembly procedures and emergency procedures. The two of us worked

together as one-catching sleep in the office. A typical day would

consist of receiving the next day’s targets from 10pm throughout the

night. We had to work with intelligence for route information;

material for aircraft availability; squadron operations for crew

availability; armament for loading of guns in the specific aircraft;

ordnance for bomb loads in these a/c; lead crew assignments;

specific position of each aircraft in the formation; plane takeoff

time to make a specific time over target; and brief the crews on

what to expect in the way of enemy action.

“In addition to working all night

Col. Tom would fly lead aircraft for the entire group

(periodically). That would normally consist of two 18 ship

formations and sometimes three 18 ship formations. He never asked

anyone to do anything that he wouldn’t do. Statistics as to the

number of mission that he flew; the targets etc. are unknown to me

but should be reflected in his personnel records…

“Col. Seymour developed the

confidence in my capabilities to the extent that he was instrumental

in my promotions to Capt. and Major, plus becoming the Group

Operations Officer when he took over command of the entire group.

“Col. Seymour was an outstanding

pilot. He knew the B-26 and the potential dangers involved. I really

don’t know the cause of his crash. I do know that he passed over the

airfield on single engine (the other engine was feathered-shut

down). He made a 180 degree turn to fly downwind parallel to the run

way and he crashed on that downwind leg. I don’t know why he didn’t

land instead of flying on single engine over the runway. I don’t

recall any radio transmission that indicated he was in trouble and

can only surmise that he flew over the field to alert the crash

crew-fire wagon to be on alert and to let the tower know that he

will be making an emergency landing.

“His death was a great loss to out group,

and to me personally, since we had worked together so long. I

experienced three of these tragedies during my tour, Col. Seymour

and two of my 4 man tent mates. You never forget having to pack up

the personal effects of your close buddies.”

Col. Robert Keller was a squadron C.O. (a Capt.) in

Col. Tom’s Bomb Group. He recalled:

“We first met when he (Tom) was assigned to

the 387th Bomb Group as Group Operations Officer, in charge of all

the flight training and operations of the group. He was a handsome

officer, always meticulously dressed, and a very capable and

demanding officer. He was later promoted to the position of Deputy

Group Commander.

“On April 12, 1944 the Group Commander,

Col. Caldwell, was leading the Group on a mission to Dunkirk when he

was shot down by anti-aircraft fire and all hands were lost. Col.

Seymour was selected to be the new Group Commander.

“Not much is known about the accident on

the night of July 17 when about 1030 (pm) hours he (Tom) crashed

near the airfield while flying on one engine.”

The Telegraph Herald ran a front

page article on Tom’s death which in part read:

|

Col. Seymour Dies In Crash

27-Year-Old Dubuquer Killed In England

Col. Thomas Martin Seymour, 27, United

States Army Air Forces, son of Mr. and Mrs. V. (Victor) F.

Seymour, 1710 Asbury Street, a B-26 Martin Marauder pilot and

commanding officer of the Tiger Stripe Marauder Group

“Somewhere in England,” was killed July 17 while returning to

his base after an administrative flight to another airdrome,

when his plane developed engine trouble and went out of

control into a crash three miles from the field.

This news came Monday morning to Col.

Seymour’s parents from Brig. Gen. Samuel B. Anderson,

Headquarters, Ninth Bomber Command, who was Col. Seymour’s

commanding officer. The Seymours have not had official War

Department news of their son’s casualty. |

|

|

|

Eulogized by General

Brig. Gen. Anderson’s letter read as follows: “The War

Department will have informed you by now of your son’s death

in an aircraft accident which occurred in England on the

evening of 17 July. I realize that nothing I can say will

alleviate your grief but I want you to know that your loss is

shared by myself and by all your son’s many friends in this

command. Ninth Bomber Command and the Army Air Force have lost

an excellent Group Commander and an outstanding leader.

“I am sure you would like to know how the accident occurred.

Tom was returning to base after an administrative flight to

another airdrome when he experienced engine trouble. He called

the control tower and reported he was going to pass over the

field, turn on his bad engine so as to take advantage of its

remaining power and make a normal two-engine landing. He did

pass over the field but lost control of the airplane shortly

thereafter and crashed about three miles from the field. He

was instantly killed in the crash.

“Since Tom joined our command a year ago,” the Dubuquer’s

commanding officer continued, “I have been in close and

continual association with him. As a great pilot for

aggressiveness in combat and gentlemanly qualities, Tom

commanded the warmest allegiance and regard of the men who

worked with him...”

“You have my deepest sympathy in you

loss. No one can replace Tom and I shall never forget him.”

In England 14 Months

He was last home in August, 1942. He was

a member of St. Anthony’s parish where a requiem high mass of

memoriam is being said next Saturday morning at 8 o’clock.

The last two letters Col. Seymour’s

parents received from him were dated July 16 and 17. In the

former one, he stated that he had just found out that he was

the youngest colonel in command of a B-26 group over there.

The letter of July 17, the day he was killed, arrived in

Dubuque five days after it had been written.

Surviving, other than his parents, are

his wife, a Women’s Army Corps corporal stationed “Somewhere

in Australia”, a Philadelphia girl to whom he was married

there on Dec. 31, 1942; three sisters, Pat and Mary at home,

and Mrs. James (Ann) Martin, Fort Belvoir, Va.; and several

aunts and uncles.

The Dubuque pilot was termed “one of the best B-26 pilots in

the business”, and Ninth Air Force headquarters had stated

that, under his tutelage, many Marauder pilots at his base

“learned to handle the fast medium bomber. He had been awarded

the Air Medal with three Oak Leaf Clusters, and the

Distinguished Flying Cross and had figured prominently in the

briefing of all medium bomber groups in the invasion of

France.

A recent story about Col. Seymour in the

field paper. ‘The Bombay,’ applauded the Dubuquer for

maintenance of his high standard of skill and ability since

his transfer to the Ninth Air Force group in England.

|

|

|

In a

tragic government snafu, Tom’s father learned of his death over the

radio. Victor sold subscriptions to the Dubuque Telegraph Herald to

farmers in the rural areas. He stopped alongside the road to eat his

paper sack lunch and listen to the noon news when he learned of his

son’s death.

Official Report of the accident provides

little information on Col. Tom’s crash:

|

Pilot’s Mission - Cross Country

Nature of accident – Crash into trees and open field.

Cause of accident – One engine feathered. Apparently

there was a loss of power in the good engine and the pilot was

unable to hold altitude to land on the airdome.

Description of accident – Pilot called in while still

several minutes from field stating that he was on single

engine. Eye witness report that the airplane passed over field

with one engine feathered and appeared to be going around for

a landing. On what would normally be a base leg, airplane lost

altitude and crashed. Cause of accident is undetermined. This

board has no further recommendation other than the memorandum

which states that a minimum crew of Pilot, co-pilot, Engineer

and Radio-operator be complied with on all flights. |

|

|

Lt. Col. Wright’s father was shot down in “El Capitan” in

May 1944 but was told about Col. Tom’s crash from others when he

returned after the war. Col. Wright wrote me what he had heard about

Col. Tom’s crash: “this is unconfirmed; it is only from 50+ years’

memory: Col. Seymour took an aircraft up and was doing a demo flight

and made several low passes. The last pass was a bit low and the

props impacted the ground at approximately the 3000 foot marker and

the aircraft stopped at about the 5000 foot marker and burst into

flames.”

After the war, Col. Tom’s remains were returned from Cambridge,

England and interred at Arlington National Cemetery in Section 12,

Grave 1242 on July 23, 1948.

During the war General Jimmy Doolittle said that the Group Commander

was the most important job in the Air Force.

|