|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

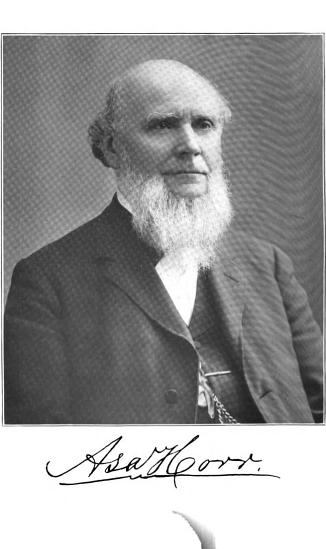

SCIENTIFIC STUDIES OF DR. ASA HORR

By James O. Crosby.

| |

|

|

After the capital was removed

from Iowa City to Des Moines, it was a long journey from

Clayton county to attend the sessions of the supreme court. In

December, 1857, Elijah Odell and I attended the first term of

the court held at Des Moines, and our journey by stage took

five days, including three all night rides.

Later the general assembly established argument terms to be

held at Davenport in April and October, for the presentation

of cases from the eastern part of the State, and in 1868

established similar terms at Dubuque. These argument terms

were discontinued in 1872, when all cases were transferred to

Des Moines. I attended all the Dubuque terms. About the first

term Judge Murdock accompanied me and introduced me to Dr. Asa

Horr (Dr. Asa Horr was born at Worthington, Franklin County,

Ohio, September 2, 1817. He studied medicine and surgery at

the town of Baltimore and city of Columbus, Ohio, and spent

his professional life at Dubuque, Iowa.), the eminent

physician, surgeon and scientist, at his office. In our

conversation the judge stated that he had recently read that

at this particular season Saturn was making the finest show of

the year with its rings. |

| |

|

In the rear of his office

Dr. Horr had built a private astronomical observatory in which was

placed a meridional telescope. With a watch, by use of the

telegraph, he kept Washington time. By the Nautical Almanac he found

the meridian time of the planet, and said if we would arrange with a

policeman to wake us at 2.00 a. m. and would go to his house and

wake him, we could come with him to the office and interview Saturn

with the telescope from the observatory, At 3.00 a. m. we were all

on hand, and while Saturn crossed the object lens of the telescope

we each had time for a good look at the planet in a clear sky, with

its rings bright and plainly to be seen.

After Saturn passed the range of the telescope, the Nautical Almanac

gave the meridional time of other stars at which we gazed till

daylight obscured them. Then we left the observatory and in the

office took up the microscope and played with it until breakfast

time. It was of good size and had six sets of object lenses of

different magnifying powers.

One slide he had prepared from fine sand, swept from rocks on the

coast of Florida. To the naked eye it seemed like buckwheat flour;

magnified, it was a collection of beautiful, conical sea-shells,

about a quarter of an inch long, with spines beginning with a light

burnt-umber color at the shell and deepening to black at the points.

Another object he had prepared was an itch-mite taken from the

person of a patient. An enlarged picture of the animal is an

illustration in the Century dictionary.

At another visit Dr. Horr told me something of his early history,

and as I, too, had had an early history, I was very much interested,

so much so that it is very clearly retained in my memory and I will

give it as of his own statement:

At the age of 19, I was working about 20 miles from Columbus, Ohio,

learning the carpenter's trade. One day I rode horseback to Columbus

to purchase a text book on botany for beginners, as I had a desire

to study plant life. I called at a bookstore and made my purpose

known to the proprietor, and he laid upon the counter a number of

books.

After an examination of them I was unable to make a selection, and I

asked the advice of the merchant, who said he couldn't tell, but

pointing to a gentleman seated in the room, said that that man could

advise me. Turning to the gentleman, he said: "Mr. Sullivant, will

you step here? Here is a young man who wishes to purchase a Botany

for beginners. Please advise him which to select."

The gentleman came to the counter and asked if I wished it for

myself. I answered that I did, and he very soon made a selection.

Then he asked if I felt an interest in such matters. If I did he had

a collection that he thought would please me, and if I liked he

would take me in his buggy, which was standing in front of the

store, and show it to me.

I very gladly accepted his kind offer and I found his home and

collection of plants large and interesting. The plants in quantity

and variety were larger and finer than I ever had seen, and his

explanations and descriptions gave me an increased interest in

botany. He took me back to the city and I returned to my carpenter

work.

About three weeks after that, Mr. Sullivant sent to me a messenger

on horseback, with a letter stating that a party of his friends,

ladies and gentlemen, at a time named, were going with him camping

on a week's outing for pleasure and research, and extending to me an

urgent invitation to join their party, and requesting an answer by

the returning messenger. I was a great awkward boy, and knew from my

former visit to his home that his company would be of a class with

which I had not been accustomed to associate. Bashfulness came over

me like a blanket. If he had sent his letter by mail, I could easily

have answered it by mail, declining the invitation with thanks; but

he had sent a messenger specially to bring it and there could be no

mistake. The invitation was not merely formal and he surely desired

me to join the party, doubtless for my benefit, and I could not do

otherwise than send an answer of acceptance.

At the appointed time, at his home, I joined the company of cultured

ladies and gentlemen by whom I was politely and kindly received.

Though it may have been imaginary on my part, I thought I detected a

slight air of condescension on their part.

After we had been out a couple of days, a discussion arose

respecting some action related in the Iliad. The controversy was

growing somewhat heated when, to avoid unpleasant feeling, one of

the gentlemen proposed to end the discussion by referring the matter

to "our young friend" and letting his decision end the matter; to

which they agreed unanimously. It so happened that I had just

finished reading a translation of the Iliad the week before, and

very much to their surprise I promptly related Homer's account of

the matter. The imaginary condescension disappeared and their

cordial treatment made me forget that I was ever bashful.

One day as Mr. Sullivant (William Starling Sullivant was born near

Columbus, Ohio, January 15. 1803, and died there April 30, 1873. He

was an American student of nature who became distinguished as a

biologist.) and I were alone in a boat on a lily pond, gathering

lilies and searching for other water plants, he related to me the

incidents that led him to the study of botany. He said: "When a

young man, by inheritance, I became the owner of the farm on which

my present home is situated. I had no plan of life and was rather

inclined to be gay and associate with young men fond of a good time.

One day I had four of them at my home for dinner and a little

jollification. Looking out of a window that showed the pasture in

the landscape, I saw a man walking slowly along, closely watching

the ground, occasionally stooping down as if to pick up something,

stopping to examine it and then putting It in a tin case which was

suspended by a shoulder strap at his side.

I wondered what the man found of so much interest in the pasture,

and said to my company: 'Boys, excuse me for a little while! I see a

man down in my pasture and I must go down and see what he's doing

there.' So I left them and went to the pasture. I found a man

somewhat advanced in years who explained that he was studying the

flora of the state, and had already found in my pasture some new

plants not yet described, that he would add to the list. I staid

with him till near dinner time, asked him to take dinner with me and

he consented. I wanted to see more of him, and if he were not

accustomed to our style of living, it might be some fun for the boys

as his clothing was suited to his work. When seated at the table,

his dignified bearing and intelligent conversation kept my other

guests as attentive listeners, with no thought of making fun at his

expense. I asked his permission to accompany him the rest of the

day, and adjourned the frolic with my gay young friends. That

afternoon opened a new world to me and led me to become a student of

nature."

The week's outing was a delightful one and opened wide to me the

book of nature of which I became an earnest student. After I had

acquired the profession of medicine and surgery and came to form a

plan of life, I resolved to be a faithful student in the line of my

profession, and in addition, to study and keep up with the growth of

the natural sciences; that if days of leisure came after my

professional labors were ended, I would have the love of nature to

cheer my declining years.

In 1847 Dr. Horr came to Dubuque and entered upon the practice of

medicine and surgery and successfully carried out his plan of life.

He died in his seventy-ninth year at Dubuque, leaving a wife, a son,

Edward W., of Blandville, Ky., and a daughter, Mrs. Charles G.

Stearns, of Waterloo, Iowa, all of whom are still living.

~Annals of Iowa, Vol. XII, No. 3. Des Moines, Iowa, October, 1915

~transcribed by Sharyl

Ferrall for Dubuque County IAGenWeb |